by Rebecca Greenes Gearhart

The Retention Pond

1.

Sixteen years ago, my brother Ethan was swallowed by a retention pond. After that, my mother had five of us kids left. The high school closed the same year. I was in ninth grade. Now my mother and I spend most of our time hiding in our trailer or circling the pond at the back of the park or taking turns driving the car into town for work. I work at the diner and my mother works the cash register at a store. She works at night, and I work in the day. Once there were a lot of families that lived in this park, but now there aren’t.

2.

I pull on a long sleeve shirt because the mosquitos are bad, especially in the dark. The park was nice once; now it’s overgrown and in disrepair. Every year that passes means it’s harder to get to the retention pond. The grass is tall and difficult to walk through, and in the dark it’s hard to see the snakes. I try to take a different path each time. It has been sixteen years since the high school closed and Ethan disappeared, but I still find new ways to walk every night. I’m already overheating, but the insect bites on my neck and on my forehead stop me from rolling my sleeves up. When I get to the retention pond, I sit in the lawn chair; it’s uncomfortable because my back is covered in sores. My back is covered in so many sores that I am in pain whether I lean back in the chair or not. Some of them are open and some of them grow a thin film after a while. I’m not sure what they are from. My mother doesn’t have them, but she didn’t seem surprised when they came to me. I wonder if any of my brothers had the sores, too.

I had a boyfriend for a long time. His name was St. Thomas, and he only stopped coming around a few weeks ago. It’s possible he disappeared into the retention pond, too, but I think he just fell in love with somebody else. He used to help me manage the sores. When the ones covered in a film needed the pressure relieved, he’d pierce them with a buck knife, and he’d make sure the open ones that I couldn’t see stayed clean. It’s hard to manage a disease on your back by yourself.

St. Thomas is not from the park, but from the town. He works for the fire department. Every time one of my brothers disappeared, the fire department would send him to come look around and ask some questions. So, I got to know him over the years. When Ethan was swallowed by the pond, St. Thomas was very suspicious. “It’s too shallow,” he said, “for anyone to have disappeared in there.” But by the time there were only three of us siblings left, he would do his questioning in our living room over dinner. And he started to come around just to check on us. “Has the pond captured anyone else lately?” He always sounded like he was teasing.

When I turned twenty-two, I had two siblings left and St. Thomas’s hair was starting to turn grey at his temples. “Would you like to see a movie?” he asked me. I looked at my mother and she shrugged. I was an adult, and she had a lot on her mind. He picked me up that evening in his truck. There was a case of beer under the passenger-side seat. He reached down between my legs to grab one. We saw a movie about mutants in the desert and afterwards, in the truck, in the parking lot, he reached between my legs again.

The sores on my back sting but I do my best to ignore the pain and I watch the black, oily surface of the retention pond. I have five brothers down there. I pick up the gun at my feet and put the barrel in my mouth, just to try it out, then I put the gun back down in the tall, tall grass.

3.

On the morning of the day Ethan was swallowed by the retention pond, he woke up and texted his boss to say he would not be coming in and then he went back to sleep. Ethan started working in an exhaust shop when he was sixteen and years later, at thirty-one, he still did. Just recently he’d asked for a demotion from shift manager. On the morning of the day he was swallowed by the retention pond, he texted his boss to say he wasn’t coming in and then he got in his car and drove to the Blue Chip Casino on Lake Michigan. He had a gambling problem, and he liked a girl named Abigail who worked there.

By ten in the morning Ethan was playing video roulette, only looking away from the screen to glance around the casino for Abigail. The casino was busy, it was always busy, and if he weren’t nervous about losing his seat Ethan would have just got up to look for her. The cocktail waitress brought him another Bloody Mary, and he almost asked her if Abigail was there, but then the speaker from the tv in the front called out place your bets and he scrambled to place his bets instead. He lost some money quickly and decided to take a break. He made his way to the slot machines. The most popular ones were either ocean or jungle themed, and almost all the ocean or jungle themed slots were occupied. He found an ancient Egypt themed slot machine that gave him a good view of the bar where the cocktail waitresses would pick up their drinks, so he sat down and lit a cigarette. The pit boss was working his way through the casino. Ethan shoved a dollar into the machine. Then Abigail was on the other side of the casino floor making her way to the bar; her shift must have just started. Ethan fed some more money into the slot machine and hit the button without looking down. He tried to smell her. He bit his lip. He had something the girls called yuck mouth.

Abigail walked right past him and picked up a tray of drinks at the bar. Ethan didn’t mind. She was like that sometimes. She liked the attention of a chase.

He thought he saw the pit boss look over at him, so Ethan hit the machine again. The whole thing lit up then the face of a Pharaoh came on. When he was young, his grandmother used to play a VHS of an opera about Akhenaten for him on Sunday mornings. As if it was church. He heard it then, sitting under the Pharaoh. He went to take another sip from his Bloody Mary, but it was empty; he just sucked up air. The opera played in his head. The pit boss looked at him and then turned away, and then there was a cocktail waitress asking if he needed another drink. Yes, he said. But she wasn’t Abigail.

“I’ll be right back with that, sweetheart,” the girl said.

He still hadn’t won any money, but he wanted to see the Pharaoh again, so he hit the machine with the ghost of Akhenaten. Then there was a drink in front of him, a whisky. He didn’t remember asking for whisky. “Do you know if Abigail is working?” he asked. The cocktail waitress shook her head no and walked away. Ethan knew she was lying. Abigail was out there on the floor. He’d seen her. He pushed himself up. He was a little shaky. He grabbed his drink, and he took the ticket from the machine that said he had one dollar and three cents left to play, and he went to go find her.

4.

At night, behind the register, my mother sits on a stool holding her breath for the entirety of her shift. The store where my mother works is the only one open late in the area, and for that reason they sell a little bit of everything: cigarettes, chips, newspapers, engine oil, protein shakes, stuffed animals, keychains, gift cards, pepperoni pizza, wine, Band-Aids, cupcakes, medical gauze, cat food, condoms, winter hats, sun hats, and more.

5.

My twin brother Angel was the only one home the night Ethan disappeared, and he couldn’t even tell us what happened. My mother was hysterical. “There is no way a thirty-one-year-old man was swallowed by a retention pond,” she cried as the fire fighters crouched down at its edge, trying to see the bottom.

“Should we drag it?” one of them asked the fire captain.

“Drag it?”

“Yeah, like in Law and Order when they have to drag the lake to find a body.”

The fire captain shook his head. “If you want to drag it, do it on your own time.”

Pretty soon after that the high school closed, so we were home when it happened again.

After Ethan disappeared, our next oldest brother, James, started sleeping in the living room every night. Nobody cared. We used to be a big family and there were never enough beds to go around. At night, Angel and I would whisper about it on the bottom cot of the bunk bed we shared.

“James thinks it’s the retention pond’s fault,” Angel told me night after night.

The retention pond wasn’t visible from our trailer, but still, James stayed on that couch looking towards it through a tiny window. Eventually he lost his job. He hardly slept. I also hardly slept.

“Does he hear it calling him?” I asked Angel one night.

“Of course not,” he said. “It’s a retention pond.”

Still, I could tell James was scared of it.

One morning we woke up and the couch was empty. The tv was on, and there was a warm six-pack and a piss jug on the floor, but James wasn’t there. My brothers and I ran to the retention pond, but the black water was still. We went to the green trailer behind the pond where a man our grandfather’s age lived and pounded on the door. He opened it. He was stark naked.

“Did you see our brother?” I asked him.

“The dead one?”

“James.”

“The dead one,” he said, and he started to push his door closed.

I pushed it back open. “Ethan is the dead one.”

The old man shook his head no and pointed to the retention pond.

“He killed himself?” Angel asked.

“No, he went in on his back,” the old man said. His flaccid dick hardened. I let him slam the door in my face. I didn’t know what that meant.

“Why does it want my sons,” our mother cried when we woke her up and told her.

6.

St. Thomas lives in a small yellow house next to a gas station in town. His house has been there longer than the gas station, longer than the shop, longer than the trailer park, and longer than the retention pond. When St. Thomas was small, he lived in the yellow house with his aunt, who herself was born on the house’s kitchen table. He spends his evenings at that kitchen table writing about the brothers. He cooks on a Monday and eats from the pot that sits on the stove all week.

St. Thomas is a firefighter but now there are hardly any fires because there is hardly anything left to burn, so he does other things. He investigates drownings, helps move dead bodies from their homes to the morgues, sometimes he’s the bouncer outside the bar, and sometimes he’s a detective.

St. Thomas never wrote anything down, not a grocery list, not a note for work, not his address, not his name. He never wrote anything down in his life until the first day he was called out to the retention pond because it swallowed Ethan. He and the other emergency response workers sat at its edge looking for the bottom. The town records said it was only five feet deep, but it looked like it went on forever. When he got up, he could see an old man peering through a window at them. That night, St. Thomas went home and wrote down everything he saw that day.

He sits at the kitchen table where his aunt was born and looks through nearly two decades of notes. There are maps of the trailer park, updated over the years to account for those who moved away, for the chunks of the park that fell off into disrepair. There are family trees that show the mother and the brothers and all their fathers and their fathers’ fathers. There are lists of things Diana said in her sleep; there are drawings of the sores on her back. There are drawings of the mother, too, crumbling over the years. St. Thomas tallied the number of bullets in the home every time he visited, copied down the family’s grocery lists in his notebook. He has the names and addresses of anyone who ever sent them mail or a package, the behavioral notes from the brothers’ report cards, their missing person paperwork. He moves his spoon around in the bowl of oatmeal next to him and writes about the final week he spent with Diana before he left. He writes down the number of open sores she had on her back and the number of sores she had with a film over them, he writes down the number of orgasms she had and the number of orgasms she faked, the number of times he finished inside of her, the number of times he finished on her stomach. He writes down the number of beers in the refrigerator and the number on the floor next to her bed. He writes down the number of hours she spent by the retention pond and the number of hours her mother spent by the retention pond. He writes down the number of hours since the last of the brothers, Diana’s twin Angel, was swallowed, and he writes that length of time again but in days and then writes it in weeks as well. He writes: “The retention pond hasn’t claimed a victim in over a year. At this point, one has to wonder.”

7.

My mother says the gun at my feet is not for killing, although she doesn’t say exactly what it’s for. She trusts we will know to use it when the time comes. The retention pond, like everything else in the park, has grown over the years. I don’t know where it pulls water from, but it grows and grows, and at night I will sit, and I will keep watch over it until one night I won’t.

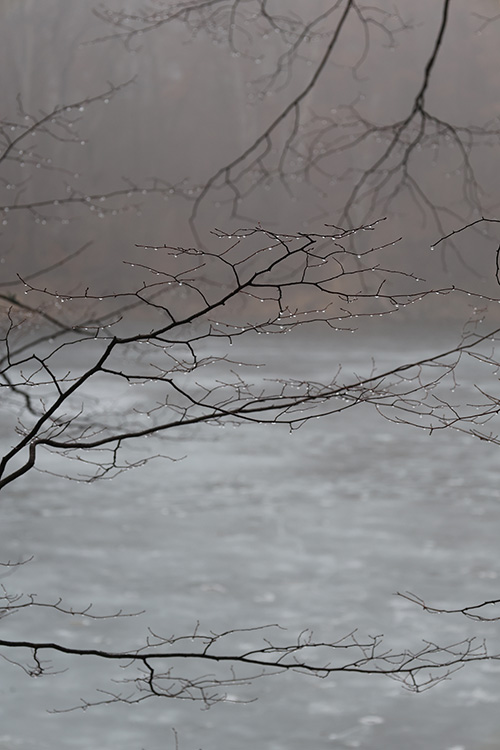

Author Rebecca Greenes Gearhart (she/her) is a writer based in the Rust Belt. Her work has appeared in The New Monuments, Islandia, The Hunger, and American Chordata. Her chapbook “Elkhart,” was published by Tabloid Press and appeared on Dennis Cooper’s “Mine For Yours” end of year list. You can find more of her work on her website: https://cargocollective.com/rebeccagearhart.

Artist Julie Thi Underhill (she/her) has published photography in positions: east asia cultures critique and Troubling Borders: An Anthology of Art and Literature by Southeast Asian Women in the Diaspora. Her black-and-white work is in the permanent holdings of the Sweeney Art Gallery, the art collection of the University of California Riverside. You can find more of her work on her website: http://jthiunderhill.com/, and follow her on Instagram @jthiunderhill.