Cantos from an Anatomically Correct Chronology

by Manuel A. Melendez

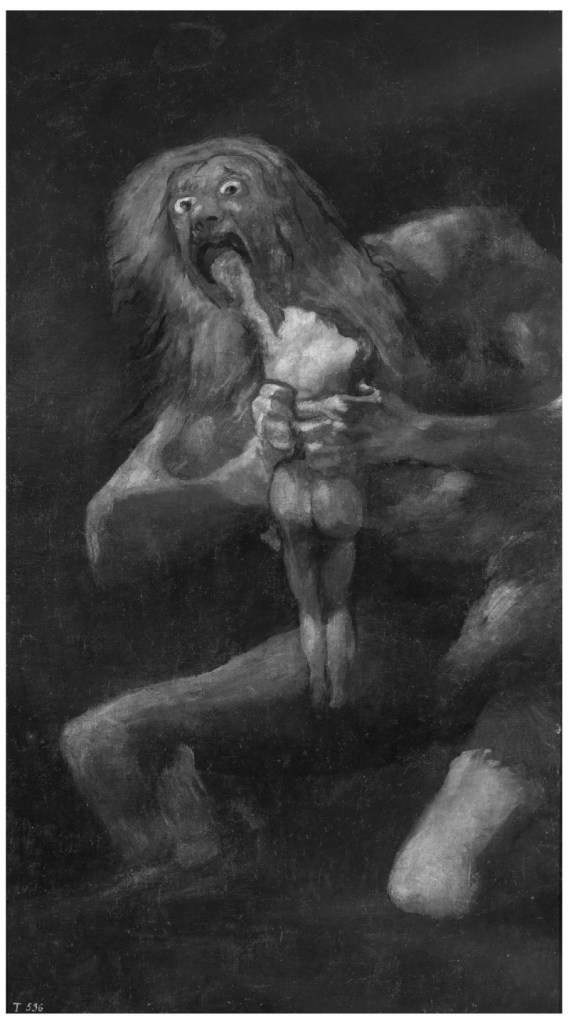

SATURN

Cantos from an Anatomically Correct Chronology

What flesh did Saturn[1] savor first?

Was it the gummy thigh by the ass-cheek? The creamy-white chest where the heart-blood is juiciest? Maybe he suckled a tender finger until the marrow gave way to a skeletal hollow. Did he inhale the meat of his son and recognize his own or did he cannibalize his godliness to sate the prophecy? Confusion persists between the Titan of this tale and the Father of chronology—Cronus[2] and Chronus[3], both typically depicted with musculatures of impossible old age, often cradling cherubic babes, the sperm that will soon be flushed, soon be digested—just the fecal matter of discussion. No artist has quite made up their mind about where on the body Saturn decided to begin his lineage deletion. It begs, then, that no importance be placed on where, but that a body is consumed whole, that a son’s topography is erased and reset, that a son is imprisoned in the bowels of his father—in that Tartarus[4] kept so filthy and so furious.

How does a son dislodge himself from that prison?

The Torso

Dover, NJ | 1996

I am zooming. The clouds glide past as miniatures of nameless towns dissolve and reemerge through the burnt orange and dishwater blue of the cotton candy approximating stratus and nimbostratus. I am, I realize, traveling the skies from the opening credits of The NeverEnding Story. Limahl’s theme song, its delectable techno-pop synth and its galactic guitar plucks, stirs from somewhere in my hippocampus and—like that—the hippo and the campus join as some beast from Bastian[5]’s bestiary, the origins and the lexicon unfurling such a creature like an incantation from invisible ink—from a wordless page inside an inexplicable attic in some inner-city school where no magic has ever been until it is—

The soaring gusts of that wind as my dad and I continue to zoom through my home on 40 Prospect Street in Dover, New Jersey—the trick my mind can play at a moment’s notice; the conjuring of an aesthetic reassembled through the space time gives us to shape reality as not itself, but as the feeling of being suspended between acknowledging that I will never learn to fly and that ineffable wonder of flying, flying, flying.

When I was eight, the only real way my dad could get me into the bathtub was by carrying me. He’d wrap his hands around my torso and waited until I stretched out my arms like a plane before swooping in and out of door frames, weaving his way around our home in Dover while I pretended to be an engine stuttering to life before roaring as loud as I could until he’d drop me back on my feet, ready to undress and get clean. He’d clutch my ribs so tightly, despite knowing that I, bony boy, was not weight enough for him to drop me. We were both very clingy then.

____________

2006

The early morning my father drops me off at Miami International to head to college, it is, of course, nothing but rain. The clouds were no longer the color of confection or confetti but dim and darkening—heavenly, empty silos. Otterbein is where, in my junior year, my AP English teacher had encouraged me to apply because I was Hispanic, and they were going to throw money at me to attend (she was right—but only about the first year). Leaving the state had been a point of righteous contention with my father, who insisted in ever-increasing bellows that I did not need to travel 1,169 miles to continue my education, the education he had insisted, on so many occasions, I could never let falter. I don’t allow the reality of his anger to sink in for a long time: he understands that he has driven me as far away as Ohio with his inexorable rampage through my puberty. The only other school I had applied to was Eugene Lang in New York City; they had said yes, too, but made no promises about money, something my father had also established to me, from an early age, would be an unending preoccupation, a kind of hostile takeover that would only ever see ceasefires in erratic spurts. I don’t look back at him as I cross the security gate.

Years later, when the resentment eighteen-year-old me carries in his luggage has evaporated into tucked-away mist, my father tells me that he watched me walk until I was a tiny, banal dot in the sea of other dots at the departure gates. He tells me he walks back to the car and drives as far as the first intersection, where his tears physically impede his ability to see the road, the sobs erupting from his diaphragm. Maybe it was he all along who taught me how to find my voice on my own. Maybe this all happens as I lay my head on the passenger window of the American Eagle plane, feeling it curve out briefly towards the Atlantic, before reaching cruising altitude, completing the ascent as rain cascades onto the retreating Miami.

____________

The Feet

Camagüey, Cuba | 1994

El Casino Campestre is the largest urban park in Cuba, and it was my playground for the first seven and a half years of my life. Every few feet within the park, speakers lined the streetlights, and the radio would play whatever music was popular at the time. In my case, it was whatever music was popular four or five years earlier in the States, communism rewinding us like a time-machine, every new day less of a future and more of a return to a kind of oblivious oblivion. But the music I remember. Memory is a surge sometimes; it just keeps building until it sweeps you up in it. When I think back to that country park, it’s in the understanding of how imperfect the remembering will remain. I am too far removed now to be able to puzzle that me together, the little one that frolicked on every inch of the Casino.

Still, memory is a kindness too—and there is one complete memory I have, even now. My dad and I, the day browned out, sepia, an old-time postcard, my tiny toy shoes pattering on the cobblestone, and Elton John singing, “It’s no sacrifice, it’s no sacrifice at all.” Memory is kindness too, reminding me that my dad could let it all be simple, that when “Sacrifice” plays and he reminds us, “This is my favorite Elton John song,” he’s telling me that this memory is actually stored in two bodies.

____________

The Stomach

Dover, NJ | 2000

My father taught me how to pay attention to details; if I left a single trace of glue on a diorama, or on a poster board, I’d have to start again. He’d remind me (sometimes with a newfound sense of restraint, other times with his usual terrorizing timbre) that I needed to be perfect, lest I lose my chance at a good education. To him, a good education was an immaculate construction, an intention that superseded any chance to get it wrong, whether it manifested as a project, or a quiz, or even a sheet of composition book paper. There was no room in his head for perforations of any kind—a B+ reduced me to gutting doom.

Report card days were akin to a firing squad, my father’s voice the rifles. Once, during fifth grade, as I turned in my report card to my father on a typical Friday, both of us inside his teal ’95 Ford Aspire in front of my school, Academy Street Elementary, I watched his smile flatten as his eyes made their way to Mathematics and the accompanying C+. I’m not sure I’ve ever felt as cramped or trapped as I did that day inside that car.

“A C+?”

A pause that even upon recollection brings the pit back to life—a sudden and blackening maw that I would spend a whole day attempting to close, my rib cage tightening and stretching as if on a rack.

“A C+?”

I admired my father’s talent in forming this question, which he often repeated, into an unfathomable reality. There was no envisioning of a universe that could hold his son and a C-average in mathematics in the same hand; no reconciliation was possible there. This surreal science-fiction was present with him in that car, a pale green ’95 Ford Aspire, and on that particular occasion, it was also part of the manner in which he would find the way to feed me guilt or shame at having disappointed him.

“What else are you supposed to be doing but study? That is your one job!”

My father reached into the backseat and showed me the unmistakable white VHS clamshell with the ripped ticket stub Blockbuster logo in its royal blue and yellow, his hand twisting it around curtly, an aborted attempt at a flourish. He had stopped by on his way to grab me from after-school care and had rented me my favorite movie of all time, The Fifth Element, as a reward for what he assumed would be a stellar (read: perfect) report card.

The clamshell case acted as a witness to my shame, but also an indictment—a victim of how the impenetrability of math let me slip further from any grip on my father’s standards, imposed on me and my future, which could not exist without them, or so he kept sermonizing every chance he’d get on long car rides or even just short ones to Pathmark or ShopRite[6]—back when I still believed my father needed me to assist him with groceries. Before it hit me that he could never divulge how much he just wanted my company; the son who was shutting all the doors behind him as quickly as his father could open them.

When we got home, my father continued the tirade. As often happened then, we rode inside a detonated silence, ashen and cavernous, and I refused to look at him (though my peripheral vision, astoundingly clear even now as I write this, could always make out the tightened knuckles as he drove). But at home, with my mother in the kitchen, or smoking out on the makeshift second-floor patio in the back of our half of the shared duplex[7], my father was always reinvigorated, always demanding to be heard. I went straight to my bedroom, which had no door of its own; neither did my parents’ room, connected directly to mine so as to make it impossible for them to not walk through it in the morning or later at night. I sat in front of my television with my Blockbuster rental and waited. I cannot remember what for, except that it felt, as it feels now when I return to this mood, that I was no longer inside my flesh, but slowly peeling away, perhaps into the popcorn ceiling or my bedroom’s chalky walls, or the inside of the handful of VHS tapes I had neatly lined up next to my television—or, maybe just becoming negative space, the absence of myself. I did not want to be the fly splattered across our kitchen tabletop. Sometime during this dissociative episode, I heard my father’s heels storming across the carpeted floor of my bedroom.

“Why aren’t you watching the movie?”

A voice full of flattened disgust.

Inevitably, when you fall through the pit you create for yourself, whether it’s despair or panic, you find yourself tumbling upward again through the esophagus, then the throat, a swelling that bursts out. I began to cry.

“I don’t deserve to watch it!”

Over and over, the litany my father had taught me to repeat silently, somehow. When crying turns to sobbing, it often feels like I am made of fleshy parts, spongy and so absorbent, the world thin and submerged so as to turn to white noise, the static of indistinct chatter, of vocal cords as chords that cannot translate language. I did not hear anything until my father, who had left my room as soon as I began to cry, returned sometime later, and in a calm, almost warm voice, repeated, “It’s okay. It’s okay.” My mother’s doing. Of that there was never any doubt. When I eventually inserted The Fifth Element into the VHS player, it was the only time I was unable to escape into 2263 New York or Fhloston Paradise. I had almost allowed my father to ruin something that was (and remains) perfect to me. It must have been there, in the aftermath of yet another encounter with my father’s hurricanes, where he also taught me about the mundanity of fear—of how even the corroding dread I felt under him could be escaped, even vaporized.

In that voice in my head, my father’s tone, his repetitions, his ritual of indoctrinating perfection, I discovered the first chink in his impenetrable armor. I learned where I could wound him. I learned how to become monstrous too.

____________

Dover, NJ & Hialeah, FL | 2003 & 2006

“Idiot!”

My father’s bellow at my closed bedroom door after I had forgotten to tape his soap opera while both of my parents were out for the night (the inane quality of forgetting, even for a stupid, childish mind). Memory is not a fickle beast here. I promised myself I would never let him get to me in his rage. When I shut my eyes that night (those freshly cut limes), I squeezed them until they could not bitter me.

But like all promises, it’s a gradual process; an extension of goodwill, bad luck, and old habits married together. My nature was as ingrained to shun my father’s howls as it was to loathe the slam of the front door in every home we lived in. Even now—even after all this time. The memory our flesh and muscles keep, our sinew and our fibers, the delicate particle logic of you or me.

In fifth grade, years before my father and I really began to come to blows, I received my first (and only) A+ in a math class. To get it, I almost created an ulcer. Growing pains were already particularly lacerating during this time; every few months, I’d have to miss classes so my father could drive me to the kid doctor with his plastic, pastel seating and easy-bake ovens and tell me I was a growing boy, that’s all, that this menthol cream will help me feel better, before I was whisked home to an afternoon of Rugrats reruns and a tenderer side to my father. These growing pains began as far back as our first apartment in Dover, 9 East Blackwell St., when I was still in third and fourth grade. When I started fifth grade, my stomach trouble began in earnest—lashes like a razor, searing my belly from the inside with splashes of fire, a dormant volcano clawing back to life through my insides.

These happened less often, but they were a piercing reminder of the cost of meeting my father’s demands. It was always my mother who would pick me up from school when the nurse would finally relent, admitting there was nothing she could do for me as I kneeled or slept in a fetal position at her station, holding in the nausea and the scorching gnaw from deep in my gut. By the third or fourth time the doctor informed my mother that I was showing signs of an ulcer, but that there was no way I could be presenting one at such a young age, not really. She was also adamant that stress could not do this alone and kindly prodded my mother about my eating habits and nutrition (my mother, bless her, did not tell the doctor that I once ate dinner because my father had told me to—despite my insistence I hadn’t been hungry—only to puke it all up; some things are just more difficult to understand inside an examination room). I watched my mother nod and respond in her respectable but broken English, understanding now as I write this how my father’s envy manifested, how he spent so many years believing I loved my mother more—her watery eyes, her thin frame (she had yet to gain her American pounds then), the incandescence of her voice in that room that is nothing but pale blue smoke now, a vanishing, a kind of flash bomb that leaves just enough light for what comes next.

The A+ in math had come and gone, and so had my father’s smile, his pride. Promises take time to build a home inside of us; they are a gradual process. I promised myself I would find a way to make my father proud, and I promised I would never make myself sick again for him.

For no one, not even myself. It took many more years for that final part to sink in.

I stopped responding to my father’s scolding taunts when I was in high school, dousing the study with Hawthorne Heights’ “Ohio is for Lovers” after our endless, escalating fights that always climaxed with my father’s favorite exclamation, “I’m not paying a dime of your tuition, you got that?” I swear my father must’ve been going deaf since middle school, unhearing, unable to listen to my pleas or promises, not even my proposals—not about my absent As in math not preventing me from getting into college, not about how I’m sick of being compared to other boys my age or younger, hearing about my crooked teeth, my bad posture, my inability to cross my legs without looking like a sissy. A fag. I heard his thoughts every time he’d lower his voice to introduce himself to a stranger, especially if they were another man, or in his dictations to my mother when I was stepping out of the boundaries of manhood he had erected for me—a doll snatched from my hand and a curt, “Boys don’t play with dolls,” as scripted and as rote a delivery as he was capable of, almost as if I could blink and the set dresser or script supervisor would suddenly be with us on this set of Our Life, the kitsch of almost believing the words he was saying. My father quickly learned I could no longer be winded by him, that I would soon commence with my own wounding, till we were both beat. He would call it “dead fish eyes,” my blank stare as he whirled like a tornado round whatever unfortunate room we were trapped in. Nothing made him more upset than my silence. I wish I had been more belligerent at an earlier age, encouraged my father to stop pretending for my sake. Instead, I threw Barbies down two or three stories and pretended they were stunt women in a film I was making up as I went along.

____________

The Eyes

Westerville, OH | 2010

Sometimes, back in high school but more intently during college, when I’d get bored, I’d practice my fuck-me eyes. The look that would, eventually, land me my first one-night stand—some boy with baby blues I won’t name, some boy I toe-sucked and savored, some boy with a template for a face—and the elation at having practiced was worth the shiver and the thrill. The same boy would start dating my best friend at the time, and I wore pettiness like a coat, incensed that I couldn’t get it fucking together, that somehow, I was worth the time in bed but not anywhere else. So, I seduced the boy—again. My fuck-me eyes were well rehearsed, and I showed even myself the ruthlessness of being hungry. It must’ve been just months before our final weeks as seniors at Otterbein, but I put that boy’s toes in my mouth again, and then everything else. Did I take his briefs off or did I imagine them back on to feel better about what I was doing to my best friend? All I remember is how delectable he was, the taste and musk of him all over punctuated by the immoral, downright nasty disregard for anyone’s feelings but mine.

I apologized to my buddy the day we graduated college, but I still justified it by reminding him of what a slut his boyfriend proved to be. That gave us a good laugh; we both knew it was only half the truth, that I also just wanted to fuck around and—further down the line of jokes—that I wanted my friend to suffer, to not be content. He lives on the west coast now, is married, has boyfriends, and reminds me of our catalog of inside jokes like I remind him. But I haven’t seen him since that day. I enjoy that castigation—that constant miss. It wasn’t just as a punishment to myself for knowing what would happen—the boy, unable to keep the awful secret of what we had done (and the luridness of that still excites me, as if I’m finally the heroine in my own Almodóvarian[8] noir), revealed it to my friend himself, atop the staircase of their fraternity, which I had been visiting that night. The babble of tears and half-sobs, then the dread silence, then the puffy, redness of my friend’s face, seething, asking me to leave. I was not a good person—and I reveled in that, I had no regrets. It felt like a lesson I had learned from my father, or rather, I had learned in the fissures of his tutelage, the curtail of my humanness for the sake of an animal that, I will continually discover, can never be satiated.

____________

The Throat

Miami Beach, FL | 2007

I sit in the movie theater with my dad, watching the final reel of La Vie en Rose (La Môme as it is known internationally save for the UK; it is French for “little sparrow”). The final crescendo of Édith Piaf’s “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien” echoes in my eardrums still. The day is a truce—our cold war is not yet over, but it is thawing. We decide to go to the Regal Theaters in South Beach because it is the closest location playing the film, an adaptation of Piaf’s life starring Marion Cotillard. There are maybe two or three other people in what is otherwise an empty screening room. It made sense an hour and half or so into the film why it would be so ill-attended (at least in the States)—this was not a traditional biopic, and the director, Olivier Dahan, was taking us on a discombobulating, non-linear narrative. I began to stop thinking of Piaf as anything but a series of memories and emotions—as an accumulation of a life through memory and through fabrication and through simulation. Even at nineteen years of age, I knew I had found someone who got the work of memory-making—of living inside memories. Who are we outside the flesh, this body that we speak out of, that often does speak for us? Who can know me in it if not me? Who can know me outside of it and still have an approximate understanding of who I ever was or could be?

I was in a daze when my dad and I walked back out onto the noisy Lincoln Road, the second most famous strip of stores, restaurants, and Art Deco architecture in South Beach. We headed directly to our usual stop, Books & Books, just a few blocks further into Lincoln Road from the theater. In their café, I usually order some assorted sandwich without the cheese and a lemonade, always garnished with a mint. I don’t remember us talking about the film then, but there was a palpable recognition that what we had experienced in that screening room was an intensely private thing, a momentous breakthrough that neither of us could grasp through syntax or vocalizations. It was its own strange enchantment; I could also feel myself pushing my dad away, refusing to look him in the eyes but acknowledging his presence with cordialness and even the first inches of tenderness a son might proffer. But memory is a fickle beast, and I know now how cruel he taught me to be. How cruel I could be with him.

And yet, even with the space between my dad and me still yawning between us, I felt La Môme’s eyes gaze out into the dark of the cinema as I munched on my sandwich and sipped my lemonade. I could watch my dad and me gazing back, both of us weeping as she sang triumph from an impossible life, a life full of misery, of beauty, of the hard realities that come with a world that cannot care for you but that adores you, and worships you, and keeps you immortal—it was not that her life was unbearably tragic, though it was—right there as she, barely able to stand and shivering, was helped to her final stage and then to her deathbed—but that I finally comprehended then why I would always love Piaf. It was more than a musical voice we could share, my dad and I, —but a promise we could keep, silently.

____________

Anywhere, Everywhere | 2025

Every time my dad calls me, the inimitable intro from “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien” plays. Every time, I allow myself to feel forgiveness. What it is—that immense crush of unwavering love.

No, I regret nothing.

____________

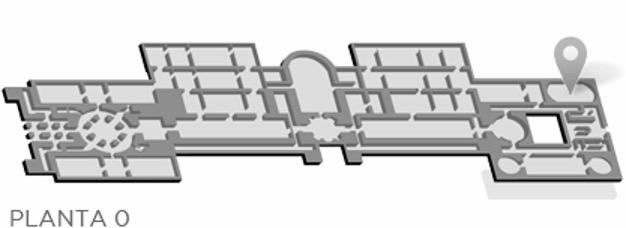

The Head

Near the end of our three-hour walk of del Prado, acting as tour guide more so than son, I lead my parents to Room 067 on Floor Zero, and don’t say a word to them about it. To get there, I have to navigate the labyrinthine corridors of the museum, its white Neoclassical walls dizzying in their blandness, an endless paintbrush circling a white smear across one’s vision an appropriate condition for highlighting the innumerable masterpieces within each floor (each divvying up decades of European art in chronological order—from Floor Zero[9] all the way up to Floor Two). But my sense of direction has always been impeccable, and I get us to the bowels of del Prado without a fuss.

Room 067 is one of the most-visited museums because it houses Goya’s most iconic singular painting, The Third of May, 1808, as well as Goya’s celebrated collection, the Black Paintings[10]. These paintings were never meant for the public eye, nor were any of them ever named during Goya’s lifetime, but they reside forever now inside one of de Prado’s darkest chambers, illuminated only by an octagonal ring of white LED lights cast upon the paintings housed inside, the licorice and dark chocolate of the marble floor resplendent even in the murkiness of the room.

I know my mother is done taking in the sights due to her bone pain (a reprisal of the cancer that betrayed her body in 2010), and we all need lunch. I get to Room 067 first, my mother lingering in the rooms behind me, but I know my dad well enough to sense his eyes on me.

“Allí está[11].”

My dad’s reverence when he finally spots the Goya[12] is a banquet, every morsel of his passion for art claiming a place in the sound of those two words, in the shape of them as they resound in the quietness of the room. I can savor them even now, observing myself observing, knowing my dad will take his place on my right, both of us eager to feed.

Footnotes:

[1] The Titan, Cronus, in Roman mythology.

[2] Rubens’ Saturn devouring a Son

[3] Mignard’s Time Clipping Cupid’s Wings

[4] The abyss where the Titans were imprisoned by Zeus and his brothers.

[5] The protagonist from The NeverEnding Story.

[6] Pathmark and ShopRite were widely found supermarkets in New Jersey during the ‘90s; ShopRite is still abundant, but Pathmark not so much.

[7] Our home on 40 Prospect St. was an oddity: we shared the basement door with the landlord, a surly man named Archimedes, whose son, Jason, older than me by a couple of years, would often come up to spend time with me (we would eventually become friends). They could come up, but we could not come down (we had no key). As the house was at the bottom of an incline, the front door of our half of the house was on the ground floor, but the backdoor in the kitchen led out to a porch overlooking a second floor onto a sizeable field full of junk and a nondescript shed where Jason and I once hid to look at a muddy, worn-down Playboy.

[8] As in Pedro Almodóvar.

[9] Floor Negative One exists but only three galleries belong to it—all of them relating the history of the museum.

[10] Named as such for their striking dark tones, predominantly a combination of burnt yellows, charcoal blacks, rusted browns, and grey-greens; Goya achieved their distinctive palette through chiaroscuro, applying wet paint on top of a still-wet layer of paint, and, most importantly, by painting directly on dry plaster on the walls of Quinta del Sordo (Villa of the Deaf One), his estate, from 1820-1823.

[11] “There it is” in Spanish.

[12] Saturn

Author Manuel A. Melendez (he/him) is a hybrid writer born and partially raised in Camagüey, Cuba between the Teatro Guiñol de Camagüey, where his father acted and puppeteered, and the Biblioteca Provincial de Camagüey, where his mother let him run loose with books. He received his MFA in Poetry from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He has been published in Apricity Magazine, The Bicoastal Review, Midway Journal, Superstition Review and others. In this life, he will settle for being penniless but ravishing on his deathbed. He can be found on Instagram at @marvelzednelem and on his website, http://manalemel.squarespace.com/.

Artist Asem Moustafa Ahmed (he/him) is a New Jersey-based artist specializing in painting, portraiture, and figure drawing, with additional interests in sculpture, printmaking, and jewelry-making. Born in Marrakech, Morocco, and of Egyptian heritage, Asem moved to Jersey City at the age of nine. Immersed in the vibrant visual cultures of North Africa and inspired by the diversity of his new home, he developed a deep passion for art from an early age. He studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and later earned his Master’s degree from the New York Academy of Art, studying under artists such as Dan Thompson, Mario A. Robinson, and Randolphlee McIver. Asem now works from his studio, creating richly textured and expressive works that celebrate the color, form, and spirit of the world around him. You can find more of his work on his website: http://www.asemfineart.com/.