by Laurin Becker Macios

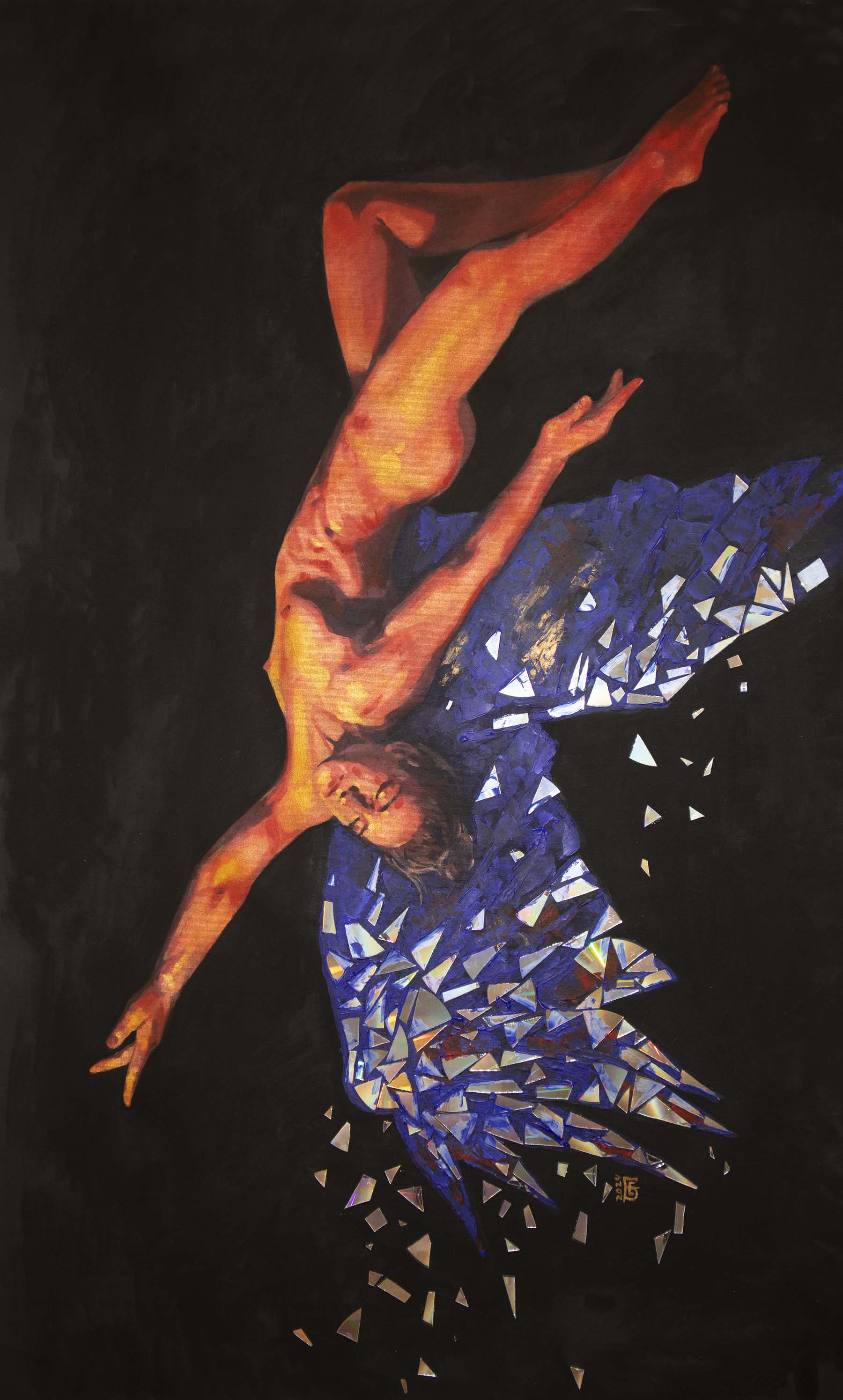

Shards

The floor is cold but spotless outside Annie’s open door. I spread myself over it, salted butter on toast, her childhood favorite.

You’re losing it, Jim tells me, stepping over me to get to our room.

By the time I manage to scrape myself up and through our threshold, Jim’s sliding his fuzzy legs into the crisp envelope of our just-ironed sheets. (Ironing is the one task I met today, that rare bout of energy draining with each vanished crease.) His face is a crumpled pillowcase, damp. I have to open tomorrow, he says by way of goodnight. Shift manager called out sick. He turns onto his stomach, eyes feathered-down, bleak reality black.

I walk slow back to the dining room, to the farm table lengthened with a leaf, to the inherited food-strewn china scattered across eight place settings. In the center, a pair of twisted white tapers still burn, relocated from the mantle. We celebrated my birthday tonight—a small one, 42—only nothing now feels small. Regardless, dear friends gathered, Jim-invited, the table set with perfect measured margins, everything in its place—gem lettuce served bright with lemon, pepper, pecorino; penne arrabbiata glopped with a grabby pasta spoon. Square-sliced, the finale: tiramisu, a candle in its center. Offkey song, sweetened decaf espresso, brandy. I stomached what I could. Smiled.

It went fine but for the relentless tentative lilt that has infiltrated our lives. No matter the topic, no matter the time, each of us knows what each of us is thinking. (Nothing new? Liz’s breath in my ear at the hug goodbye. Nothing new.)

Slowly I straighten the chairs, carry the dishes in small delicate stacks to the sink, sudsing them with gloveless hands in needlessly scalding water. I close out the candles, watch the grey smoke swirl, then collapse on the couch, where I’ve taken to sleeping, since my book light bothers Jim.

My hung head jutting up, I wake with a start, a shimmer of saliva escaping. I’ve dreamed of Annie’s face again, the dream in which her mouth’s a mossy pond.

Casco Bay black, I crack a window to hear the waves, to breathe them. There’s a foreign flicker on the horizon, a small orange flame. I realize I’m seeing a reflection. One taper I’d blown out, now somehow re-lit on the dining room table. I watch it for hours.

I know night’s over when Jim enters, his Dunkin’ shirt on. Being the owner, he doesn’t have to wear it, his uniform of 20 years, but I wouldn’t recognize him in daytime otherwise.

Jim, I say, pointing to the candle, explaining. Obviously, it’s her, I say.

Jim blows it out, walks away. Maybe get out of your head, he says halfway through the screen door, and rake the berries.

I breathe in, out, count the seconds. I make fists, unclench them, pour coffee, sipping instantly to feel it scorch my tongue. Jim’s not wrong—the crop is close to wasted—but its symbolic ripeness breaks me and I can’t seem to make myself useful. Meanwhile, he’s become his job, developed a few new hobbies.

Midday, what I can muster: the table leaf needs taking to the attic. Up the pull-down stairwell, a single lightbulb spits a narrow light. I hoist its weight, grope at visibility’s soft edge, the rim of Annie’s childhood trunk illuminated. I dust the lid with my palm, then against my better judgment unlatch it. Visible: unsteady penciled alphabet, soft-pilled bunny, crushed homecoming corsage. I let the lid crash, turn away, but a glare catches me—a gifted photo frame, inlaid pearl, broken. Inside it, slipped off center: Jim and me in black and white, exchanging vows in the field, my lace hem wind-curved like a silver scythe. Next to it, the plastic-windowed cardboard box that holds my dress. Preserved: lace, thread. What more?

When Jim comes home, I’m where I’ve spent the day: the shrunken dining room table, phone near-dead before me. I’m replaying the hotel footage, the last trace of her we have—spring break, freshman year, grayscale, pixelated. I no longer need to watch it, looping reel it’s become in my head. I have memorized her movements—into, out of—the young man’s room. Into, she nudges him easy, silent knowing laughter. Out of—alone, not unsmiling, she side-steps a strewn room service tray, her left hand raking her hair. She turns a corner.

Do anything today? Jim asks, cracking his sore back. I try not to pin down the tone—maybe pity, slight disgust.

I almost think I remember counting the hours—the phone call from Bahamian police three days into her trip, her friends having reported her missing. At first, time felt pregnant, like she’d slide from it soon. It’s since become a deep realm she must have stepped into. Her gait did often bow, as though land legs were hard to come by.

Jim says pleading cracks a window, air flow for its opposite, so when I do, I do so silent. In this other dimension: let her body be her own, ruby blood beating into her 22nd year, beige blunt bob tucked clean behind her small pierced ears. This is the only acceptable way to imagine her alive. (Any reason to go off grid? the lead detective asked. Jim balked, and though the answer was no, the question brought me the closest I’ve been to calm.) Regardless, the loss is a brimful bucket I can’t empty, my wish to uneven anyway. If emptied, what’s left? Questions, visions, a hunger-repulsion I can’t sate or shed.

Tonight marks five months since she disappeared. I cancel all upcoming plans, then Jim remakes them.

Morning. I wake to the self-lit taper, touch my finger to its flame. Pain. I hold it there until I can’t, run cool water on the blister.

Jim’s long gone, hours-deep at work, serving coffee and donuts to the town, the passers-through. I wonder if he saw the flame. I wander the barren, aware of my screaming fingertip, briefly curious if work is in me today. The blueberries are riper, bluer than they should be on the stem. But no. I pluck none, leave the rake leaning at their edge. I skirt the crags, the rough shoulder of the farm where it drops off toward water, where the Atlantic sweeps against and against. The sky is blue. The water, blue. Each wave, broken, loses its hue, loses its reflection.

I remember the summer she was five, the crop gull-gone, her small hand scouring the bushes, empty. For years after having her, what vexed me: that we had so much to lose.

I turn back for my favorite view: the farmhouse I grew up in, the farmhouse I now own, the red barn beside it. Swallows swarm in, a family maybe. They shatter away. And I see it now, the simple fact—that nothing can be mine. That we’re barely here at all.

Evening, cusp of night. The taper’s still lit when Jim walks in. He catches me before it, photo album in my hands. On the open page is Annie, just born, swaddled in hospital pink. For god’s sake, he says, but I don’t answer. I stay inside the memory, the circular shocking pain of it, how at the searing of her head I slipped to, not the other side, but another side, a realm of ghostly vibration where my body worked alone. I remember sleeping, chin-shouldered, watching myself from above as the doctor said push and my body, without me, did. Must have. The way our selves are multiplied, divided, misaligned.

Misaligned—something we often were, especially the later years in which straining for something frayed us into nothing like that thing at all—happy family, well-launched daughter. We stretched ourselves for and toward her, urging her own reach—past the franchise, past the farm, toward her future, future, future (college, career, love). Misaligned with her marrow, ghostpearl that she was.

She used to love to help her father at Dunkin’, charm the travelers through. Gruff guffaws from scruffed men, nostalgic women’s eyes. Age six, any sugar, sugar?, her favorite line.We sold extra with her at the counter—sprinkled strawberry donut, glazed coffee roll. Then every few minutes, it seemed, she’d announce taking my five beforestealing away into a corner squirreling donut holes.

She’d say she loved the farm less, but it was less novel. We lived it, its ebbs and flows and aphids. She’s a social creature, Jim would say, a soft knock at me. Myself, I speak with it, the barren my wavelength, my longest friend. More than most people (and I like people fine) I enjoy what the lowbush, the velvetleaf, the lichens have to say.

Morning. I’m wrapped in blanketless cold, goosepimpled. You’re torturing yourself, Jim tells me, plucking my phone from my hand, handing me tea. Earl Grey, oversteeped, wedge of lemon.

Something there might matter, I say. Switched black: the Facebook group about Annie’s unsolved case, my phone now in his pocket across the room.

It won’t. Jim’s face: retaining wall, hard and pale. Sharp-shouldered in his white Hanes shirt, he turns and walks away. It occurs to me, this view—his leaving—is how I picture him.

Today, a plan I’d canceled that Jim remade: a meet-up group for family of missing persons. How many along the coast of Maine could there even be? We go together, introduced to the group by Jim’s convivial smile. Small inside, diminishing each day, I half-moon toothless hellos.

Across the circle, over other’s talk, a man’s eyes—sorrel hue, outline of almond—find mine, find mine again. I know what compels me—the sudden eddy we two float through, soft alongside the rapids—but not what allows me—to this point a model wife. I let him hold me that way, invisibly, from my spot across the room, his amber flannel against my cheek, his salted beard bristling my skin.

Later that night I ask Jim, did you catch that man’s name? The one whose wife is missing? Cruel of me to make him draw it, I know—the deep bath of vowels I lower myself into, consonants holding taut the water.

For four weeks, group is the plan I keep, the thing for which I rise, letting shower water scald my scalp russet. Some days I towel-drag slow the length of my body, stirred to take my own touch by each fat bead of water, its easy give to fiber—how one becomes of the other, intended. Others, my nude self stands patient, penitent, cold witness, evaporating—letting the mirror reflect us both—me, Annie. She’s in the lace riffle across my belly, the slight gap between my abs, not to mention the bell shape of my chest, having served myself to her infant hunger, her plump pink tongue with each gulp rolling like a teenage eye. Not visible: the press apart of those later years, the pull—to being two distinct, linked women.

By the fifth week of group, Jim’s done. Glad it seems to help you, he says, wiping clean his new vintage camera, the viewfinder quirky at its top. But me, what I need, bent toward the lens, lining me in view, is to move forward. I hear the shutter click, worry its caught expression.

At group, the man speaks least. He listens—limestone, porous, absorbing. What do you do for fun? he asks me after, dredging the pink box of coffee.

Fun? I could touch him. I am nothing but my blood, wild river coursing.

Another week x’d on the kitchen calendar. No news. No nothing. Nothing but the candle, its constant flicker—Jim hasn’t blown it out. I come home to it, wake to it, eat before it, the morsels I can manage—a bite of banana here, dry toast there. Hunger jitters coalesce with nausea, my body welcome mostly to worry. (You’re getting too skinny, Jim states toneless, jawing tender new potatoes, a still-red filet.)

Another weekly Zoom with the detectives. They reiterate they’re sorry, they’ve turned up nothing. No leads, no body. No body, but she has one, and might still be in it. An island is finite, a person too (but a girl—a woman, still sussing her limits?). She was not always cautious—I felt that a boon. Jim would have kept her safe, always cocooned (be careful, don’t, no). Know this: I am not reckless. But that she risks small acts of living—windsurfing, free climbing, small talk, love—I treasure. She wanted to be a pilot, a zookeeper, a hotelier. Her last chosen path: journalist. Always, she’s been tender, the only real way to be strong, like the palm tree that absorbs a blow by bending with the storm.

The Zoom ends, pointless. I walk to the ocean. It seems ages since I’ve entered it, stood sure at its lip, its brackish tongue lapping my legs. I always loved a wild swim. The memory of it is visceral—feeling swallowed whole, then spat out and out and out, splayed cold on the warm sharp shore by the foaming tip of waves. Today is another day. But no.

I am afraid, frozen, stupefied, stunned. I am counting my cardinal luck, abacus easily—jolt—erased. Shorewalk, toe-dip, shell-gather, home. I shortcut through the brush, the bramble, absently plucking berries—blue, black—from unassuming branches as though they’re mine to tongue—sweetness, seed, devoured, gone.

Group. Again we drain the coffee into lidless paper cups, this time letting the heavy door clap behind us. We walk down the harbor path, as though we have a plan.

My wife and I, we were—we are—snowbirds, he says. I understand the difficulty of tense. Time split between our hometowns—Bucksport, hers; Charleston, his. No kids. In Maine, she kayaked every dawn. One morning, unreturned. He doesn’t linger on the facts, or their lack, just kind of invites her on this walk. She doesn’t come.

A fervor for numbers tallies slow from his tongue—his fun—in a discerning, slight southern drawl. They’re ancient, corporeal, a comfort, I catch, sea wind cadence.

The idea of many, as it happens, he says as we watch the clouds bleed, the sun smeared behind them, preceded the idea of one. At the soft ruffle of his own atoning laughter, something vital in me unpins. He shoos his words with a dry cracked hand. The arc of it through air is sustenance I take home.

My mind this week: flood, bliss, leaf curl, blight. On top of ambiguous loss, already a battle of grief and hope, is piled the surprise—a still-pink berry—of wanting this man.

On the couch alone, walking the beach alone, washing my face alone, raking the bush alone, I think of Annie, then bite his bottom lip—just a little—tease it like a pit. His rough hands are not too gentle, crimping my ripened nipples, clutching my skirted ass, flattening me to loam, grazing, whetting, entering. I am wildberry red with want—something I’d forgotten.

Can Jim see what I’m thinking? That I’ve taken my time in the field? I’d be surprised. His sight is usually through me—not into, just past, like I am the chair making favorite the room. Hard to help after all these years, I’m sure.

The next week after group, again we walk to the harbor. We sit this time, a charged few feet between us on the weathered wooden bench.

Placing his phone to reverberate from his poured-out paper cup, if I may be so bold, he says. Gospel. Now I’m found a choir sings. Are the unfound, unsinging, listening too?

You asked about my fun, I say. I don’t know how to let myself have it.

With her missing, he nods.

We’re quiet then a long time, but in that quiet, we’re talking.

Jim’s straight lines are no surprise—his soldier on, his upper lip. They say opposites attract. I twist, loop, meander. I am a sudden epiphyte appearing. But I’ve become something else, too. A line cast by hands I don’t recognize into opaque and teaming water.

We are doing what we can. And if it seems to drain this cove, expose the bluff between us? And if the tide has gone? And if the moon, too?

Autumn. The hummocks are bronzing. The leaves are letting their green masks go. News has come for him—a morsel—his wife’s life vest washed ashore. I guess she didn’t always wear it, confident of the kayak, the familiar path she paddled. He’s heading back to Charleston, he announces to the group. He leaves the meeting early with just a wave, almost imperceptible.

I pull the jeep into our gravel drive, no interest in going inside. Shoe change porchside, I head through the hillocks, watch high tide loosen from my favorite knoll. A chill comes through and I welcome it, underdressed as I am in a thin mohair sweater, sienna. A little snug. Annie’s.

That night with a storm gust the old barn window shatters. Jim appears with a fat brown rag—what we’ll stuff into the wound—asking, me or you?

I go, grateful for the window’s shivered edge, its sharpness to press my skin to.

Morning. I call the detectives, wanting news to be contagious, wanting some for us too. Nothing, of course there’s nothing. What did you expect? Jim says over his shoulder, off to work. It’s time to stop waiting.

That night I round the edge of a day spent ambling, wasted berries wedged between my toes, rinsed clean at the water’s edge. Doubts sing to me like birds. I envision Annie’s face, again her mouth a pond, and I try and try to swallow that water.

My feet take the pilled runner to our room. I kneel bedside, hands clasped like I remember how, then climb in, face Jim, make of myself a window, slide it open. I know I’d all but given up, feeling so often Jim’s hand drawing the curtain. But of course, nothing is easy. Everyone’s misunderstood.

Jim turns his back, clicks off his old bronze sconce.

I dream of the slivered shards unswept, catching light along the rafter. The swallows.

Author Laurin Becker Macios is the author of Calling Me Home, a Young Adult verse novel forthcoming from Holiday House in 2026; Somewhere to Go, winner of the 19th annual poetry award from Elixir Press; and I Almost Was Animal, winner of the 2018 Writer’s Relief WaterSedge Poetry Chapbook Contest. Her poems have appeared in Green Mountains Review online, [PANK], and elsewhere, and are forthcoming in RHINO. The former Executive Director of Mass Poetry and former Program Director of the Poetry Society of America, she earned her MFA in Creative Writing Poetry from the University of New Hampshire, where she taught on fellowship. She lives in Connecticut.

Artist Kateryna Bortsova is a painter – graphic artist with BFA in graphic arts and MFA. Works of Kateryna took part in many international exhibitions (Taiwan, Berlin, Munich, Spain, Italy, USA etc.). Also she win silver medal in the category “realism” in participation in “Factory of visual art”, New York, USA and 2015 Emirates Skywards Art of Travel competition, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Kateryna is always open for commission and you can view her work on Instagram: @katerynabortsova, or on her website: https://bortsova6.wixsite.com/bortsova .