by Laurie Clark

Dark Feet, Dark Wings

To go in the dark is to know the light

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

And find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

And is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

—Wendell Berry

There are no flowers or balloons in an Intensive Care Unit—just cold floors, a labyrinth of tubes and cords and wheezing machines in a room denuded of all color. Outside those walls and even on that very ward of the hospital, the pandemic with its delta variant raged, inflaming tribal skirmishes over mask-wearing. Even a country—a middle eastern battleground for a 20-year war—fell, bemoaned the US media. Yet my sister lay suspended in stillness.

Abby likened the ringing in her ears to cicada song, a constant murmuring drone. A year of migraine headaches and overstimulated senses had driven her at last to seek treatment. An MRI revealed the source: a benign meningioma deep in her skull. The tumor wrapped round her optic nerve near a major artery. But it wasn’t cancerous. If she survived the surgery, we were told, the prognosis was very good, though it could grow back.

Still, according to Johns Hopkins, 90% of patients do not see a recurrence if the whole tumor is removed.

Abby said, “If you’re going to get a brain tumor, this is the one to get.”

Her surgeon, a woman with salt-and-pepper hair, took a conservative approach to the procedure: if the tumor was too close to the optic nerve, possibly affecting Abby’s vision, she would remove only part of it. Radiation would take care of the rest.

As it turns out, the tumor was golf-ball sized, gaining in mass over the past 10-15 years. A vibrating instrument removed it all. Awaking from the surgery, Abby knew her name, took steps, recognized her husband. I arrived after her surgery as planned—right after she slipped into a coma.

Abby screamed her way out, according to family lore. My baby sister arrived howling and needy, taking our young parents by surprise.

I had been, by comparison, an eerie baby, silent as the grave for two weeks straight. The soundlessness still leaves my father helpless with wonder. Their first baby girls, twins stillborn five years before me, lie in the family plot at Grace Chapel Cemetery in rural Alabama. A kneeling lamb is etched there into tiny gravestones.

“Your mother would send me into your room to check on you at night, see if you were alright,” my dad remembers. It must have been tough, quelling the pall of doom.

But Abby set our home akilter from her first breath, a skinned rabbit with a set of lungs that would not quit. Towheaded and busting with mischief, she would roam the hallways of our house when I would leave for kindergarten.

Looking for me, bereft, she would howl: “Woy-Yay!”

When I came home from school, we’d romp through the fog in our Monterey backyard. Invariably, ice plant, an invasive coastal succulent carpeting the landscape, would leave our white socks stained green. On weekends, my folks would haul us to beaches along Big Sur. I ached for the ocean, but goosebumps burst my skin; instead, I picked through foam around the edges, hunting hermit crabs. Abby would run my folks ragged, stripping off her diaper, squealing with joy, escaping grasping adult arms and dashing straight through the murk on seaweed strewn sands.

At home, when I’d disappear into a book or construct intricate inner narratives for my dolls, she’d scowl, aggrieved. Then she’d bite the feet off my Barbies, for good measure.

My father moved us every three years or so from one army base to the next where he flew helicopters. One long summer, the four of us crammed into a single hotel room near Fort Rucker, Alabama. We wiled away time watching Atlanta Braves games at night from a small screen, pale skin browning from endless days cannonballing into the swimming pool on base.

After returning from Germany the first time—the summer before sixth grade in Virginia—my father drove us down to Florida’s panhandle on vacation. Abby and I shrieked at the hungry waves, diving and sifting for sand dollars by day; at night we drank sweet tea in cheap seafood diners. My mother would cool us down, rubbing Noxzema into sunburnt shoulders before bed.

Between moves, we would land at Aunt Wyneise’s farm in northern Alabama. We two girls ran wild, chasing stray cats and snatching eggs beneath banty hens. Sometimes we would walk the pasture, mindful of cow-patties. Or we’d fish the pond, the air heavy, buzzing with heat and insect madness. My Uncle Lloyd, a plug of tobacco wadded in his cheek, would spit brown streams, eyeing the inky surface for water moccasins.

When our nomadic childhood ended, Abby settled down in tidewater Virginia along the muddy banks of the James River in an exurb town between Smithfield and Surry. And I roamed. To New England, Alaska, the Midwest, Botswana, Costa Rica. I spent a summer poring over chapbooks in a marbled European library with cathedral ceilings. My teaching career ranged across both American coasts. Childhood rhythms kept me ambling onward.

Meanwhile, Abby brooded. As my absences grew longer, geographic distance stretching further, her sense of abandonment deepened. On a visit from the east coast once, she screamed at me on a street corner in Laguna Beach, golden light fading over sparkling waves: “Why can’t you be a sister?” Up to my eyeballs in a new job in a strange land, I barely comprehended the question. I could not stop my wanderlust, so I allowed silence its space.

I paused and took a breath before walking into her ICU room for the first time. Two violet-black lids marred a face swollen almost beyond recognition. She wore a creamy knit hat, not unlike a newborn—but grotesquely misshapen; they had removed part of her skull to keep swelling down. She had suffered a stroke. I had steeled myself for this.

But I was not prepared for her beauty.

Her skin was golden brown from days at the beach boating on the James River. When the nurses adjusted her gown after checking vitals, I could see her peeling chest from that weekend’s sun. A tattoo I had never seen, the Virgin Mary clutching a beaded rosary, wended down the forearm toward her warm, limp hand. On the other wrist, her husband Pete had taped a cracking scapular, winding powder-pink rosary beads around motionless fingers folded over a pulse reader.

Alternating vigils, Pete, my dad, and I took residence there for two weeks. We napped through nights in a vinyl recliner by her bed, bringing each other foil-covered food in plastic bags or paper coffee cups. We waited for signs. Meanwhile, her weary doctor ordered more tests.

My daily drive across the James River Bridge was the only thing that felt right: The seagrass and pine trees of the marshes gave way to gray water meeting bruised-cotton skies. Tall metal towers—stern sentinels—rose from the waters, stringing power lines. Newport News Shipbuilding stretched along the shore, an industrial scape of metal and might. Parallel to the end of the bridge runs a pier. Sometimes people, spaced apart, drop fishing line wrapped in chicken parts to lure hungry blue crabs.

The James River flows across the whole state of Virginia, from the Blue Ridge Mountains and valleys to the Chesapeake Bay, its watershed stretching over 10,000 miles. Williamsburg colonists staked claims on it for their early settlement, and it snakes through Richmond, the current capital. Today three million people reside along its banks, including Abby and Pete, who settled into a suburban home not far from Newport News Shipbuilding—she a data analyst, he a foreman in charge of submarine construction.

The first night I left the hospital and glided over the river, the sky was a tunnel-dark vacuum. Kurt Cobain sneered from the radio: “…nature is a whore.” On such dark evenings ending yet another day with no improvement in my sister’s condition, I welcomed the James’ black waters as I crossed the bridge to her subdivision. Indistinguishable brick homes and crepe myrtles wound through cul-de-sacs.

Pete’s relatives flew from corners of the country to offer support at home. Once, at the kitchen table in the middle of the night, I downed a glass of muscadine wine with a dental hygienist cousin from Texas. She poured yellow cake mix and canned fruit cocktail in an aluminum tray and called it dessert in a pinch. It’s a southern thing, she said about the wine as my lips puckered.

Lying on an air mattress later, I could hear the droning male voices after others had gone to bed. They repeated one Hail Mary after the other, the gruffest, most tender call-and-response.

At the hospital on a different sleepless night, I flew out to the central desk, eyes wild, my hair a witch’s halo: “Don’t you hear the beeping?!” I demanded, pointing to one of the many monitors pumping a steady stream of painkillers, antibiotics, and saline solution. Nurses stared back; it was just another night on their shift.

The pulmonary specialists came several times a day, pulling their portable machines. They suited up with PPE and face shields, protection enough for a nuclear disaster, to force metal tubing down to clear her lungs. Eventually, X-Ray technicians wheeled in a machine straight out of Star Wars, lifting her back to take pictures of her heart, looking for a donor match.

Once, apropos of nothing, tinny sounds—not unlike a music box or the organ from a carnival ride, or maybe the call to neighborhood children from an ice cream truck—broke the spell of the rattling respirator, the clicking and whirring monitors and drips. A nurse told us a baby was just born. At the moment of birth, a father pulls a cord from the maternity ward and the song, a lullaby, will chime over the loudspeaker throughout the hospital.

Abby’s youngest daughter was born at this very hospital 13 years ago. After the birth, I had patted my sister’s back as a nurse sponge-bathed her. Improbably back here years later, we hear the discordant lullaby twice on the same Sunday. The second time interrupts Pete as he explains the process of organ donation, how they will give Abby more hemoglobin to prep her for a possible transplant.

“Lullaby, and good night…go to sleep my little baby…”

One day I woke as a nurse, arriving for her morning shift, lifted blinds to let the morning stream in. Abby was angled toward the window—more like an object tilted toward the light. In that moment, something small and familiar shifted into place. I recalled Elizabeth Bishop’s poem about catching a fish. That battle-weary sea creature offered not a whit of sympathy or recognition to the speaker burdened with her trophy. At the end of the poem, when she decides to let the fish go, the poet insists on the word “victory,” repeating “rainbow, rainbow, rainbow.” I always wanted my students to unravel the mystery of the repetition. I imagined doves and arks: don’t you see? Blank faces blinked back.

Maybe that rainbow is an illusion, after all—just engine oil pooled in the bottom of a boat. Bilge.

The Richmond Times Dispatch once described the James River as a “sewer…where the odor of…things long dead clutches at the nostrils.” In the 60s, human waste and toxic pesticides poured into the lower James, one of the world’s largest harbors. Now decades after government regulation, the sturgeon population has made a comeback and bald eagles nest along its shores. On my James River crossings, I search the skies for these birds. But shipbuilding’s metal cranes and massive cargo ships regularly ply the waters, stark reminders of human encroachment.

On the other side of the bridge near Hampton Sentara Hospital, a skyscraping apartment building looms. In 1969, my father drove from Alabama, crossing this river for the first time to attend flight school at Fort Eustis. He said it overwhelmed his country boy’s eyes, the improbable promise of a big city.

Military dependents like me and Abby—“brats,” they call us—live on the margins of civilian society. We arrive, curious foreign specimens, strangers. Our meager possessions are locked up in storage every few years. Or movers pack them. Sometimes they steal our things. Clothing styles will be different; we’ll either be mocked or the source of deep envy, depending on whether we’re arriving from overseas or departing for another continent. We shop for cheap bargains in commissaries and live in substandard housing. Overseas, locals—especially young people—view us as invaders.

Entering civilian life meant deep disorientation. Ultimately, I could not shake the feeling that somehow I should land somewhere else keen on outsiders. Abby’s impulse was the opposite: she rooted. Somehow, we could not reach an understanding of the other. Distance grew in those spaces between us.

But our text threads over her final summer tell a different story—of two sisters floating back to each other, a thawing freeze. Out of the blue, she wanted to know if I used anything for dark undereye circles, an inherited Trowbridge trait from our mother’s side of the family. I didn’t, but I passed along my sunscreen recommendation.

Later, she sent photos documenting our father building a raised backyard garden bed, a gift for her youngest daughter. She announced: “Girls just got home. We’ve now got a freshman and junior. Getting ice cream tonight to celebrate.”

In early June, we exchanged images of our hydrangeas. Hers near the James River were purple in a terracotta vase I had sent for Mother’s Day during the pandemic. Close to Richardson Bay in California, mine opened bright pink. She liked the pink.

Abby sent candid pictures of the girls in Yorktown, heads and arms locked in stocks for the Pirate Festival. I snapped a shot near the Larkspur ferry: a mini pony standing in the open backseat of a small yellow Jeep in a mall parking lot. “Only in Marin,” I wrote. She always did have a deep regard for the absurd.

More recently, she wrote, “What’s your blood type? I’d forgotten that mine is O Negative.” In another text, she shared an X-ray of her skull, a black field with a skeleton in relief. Nesting behind the eye socket is a white circle, a cotton ball. Something is wrong with this picture. I tell her to hang in there.

She says, “Nothing a little Harry Potter movie watching won’t cure.” It would be one of her last.

She wishes me safe travels when my husband and I embark on our cross-country drive in July. We take Route 40 from Barstow, California, all the way to Wilmington, North Carolina. She can’t wait until I’m closer. I send a hasty photograph of me kneeling beside my dog from a corner in Winslow, Arizona, an inside joke.

When I don’t get a job I thought I wanted, she texted: “I’m sure you’re sad, but don’t dwell on it. Think of what you have and what’s to come.”

There are beginnings and endings. Stretches lie between.

After 20 years teaching, I am now a student again in a graduate program. Abby was taken off life support in Virginia just as my school’s orientation began in North Carolina. We three—father, husband, sister, a hobbled trinity—gathered around the bed. A nurse named Rachel—the one with her longest—handed us each an individual test tube, a printed paper copy of her heartrate buried inside, like some message in a bottle borne from the sea.

“Each heartbeat is unique, like a fingerprint,” she said.

I touched the crinkled blue ribbon she had coiled around the glass, as for a child’s gift.

Freed finally from tubes and cords, Abby transformed into her sleeping self. I held my breath when they removed the respirator, watching her struggle for breath, a gasping fish. Yet, she would find the rhythm. She would not die that day.

In early October on Abby’s birthday, I returned to Isle of Wight County for a Catholic memorial service. I took Route 10 to the church, past sunny fields with cotton bolls bursting from brown stalks. After gazing up so long during the sermon at Jesus hanging there crucified, I needed air.

I drove to trails on the margins of the James River Bridge. Still clad in funeral black, I walked beyond the overflowing trashcan at the trailhead, the air seeped in unseasonable humidity. Loblolly pines and bald cypress shot up from the wetlands. I stepped past skimming dragonflies and heavy reeds. Occasionally, a hermit thrush whistled a pensive song from a thicket. These shy brown birds perch low, lingering longer into the fall than most before migrating south. They prefer secluded spaces.

I reached the end of a wooden walking bridge and took in the river’s gray expanse. Cars whizzed across the 5-mile length in the near distance over the massive industrial waterway. Weeks ago, Pete had guided their girls here, perhaps to this very spot. I imagined the humming heat as he broke the news: she would not recover. I turned around. There’s no escape here.

I returned to my new home near the Cape Fear River in North Carolina the end of that summer in uneasy proximity to death, a ghost haunting my own life. I could barely speak.

Skimming poetry, I learned a new word: metempsychosis. The transmigration at death of the soul or a human being or animal into a new body of the same or different species.

Deep in the still of night in my bedroom, a fan whirred overhead. To stop and think would hasten the void—and I can’t afford to be overtaken. Not yet. In the distance, a siren wailed. From somewhere in the house, my herding dog closed his dual-colored eyes, throwing back his head, letting loose a sound—some deep instinctual keening echoing off walls, blending with insect hum. Gradually, it faded to just another infinite, soundless hush.

In February not even three years ago, the western North Carolina landscape was soaked, desolate, brown. Rains came, steady and ceaseless. My mother had died suddenly in a hospital the day after Valentine’s Day. Before the funeral, we sent sacrificial items to accompany her body in the crematorium. Someone offered a large Hershey’s Kiss, a favorite indulgence. I wondered if my dad had given it to her in the hospital. The oldest granddaughter presented a self-portrait in anime sketched with colored pencils, pink blossoms hovering around her body’s outline. The younger one wrote a brief letter filled with unanswered questions. And I? I handwrote Mary Oliver’s poem “Wild Geese” on a blank page. All later burned to grit and ash.

In the early aftermath of my mother’s winter passing, a numbness overtook me. Sitting on her front porch under slate Appalachian skies, I spotted Canada geese coasting overhead through clouds in the dusk. Their V-formation pointed a direct arrow over the Catawba River. The poet, too, had died that year, her words a chorus in my head caught on repeat: “Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine. / Meanwhile the world goes on. / Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain / are moving across the landscapes….”

On a rainy summer evening in Virginia not even three years later—yet again leaving my station beside my lifeless sister—wild geese glided over the hospital parking lot in twilight, right over steamy asphalt and dripping fuchsia blossoms on skinny trees. I glimpsed stretched necks and wings falling into line. Honking cries harangued me about my place among the living still.

Winter closes in and I am hunched inside a circle of light at my desk, darkness all around, my fingers drifting and slipping in a writer’s trance. Above me, there’s a photograph pinned to a bulletin board: Abby and I crouch in the dirt, birdseed in hand. She wears a little girl’s lace-up shoes, motley red and blue, like clown’s feet. Fair hair falling across my face, I’m reaching toward a pigeon, so far from me in the background. But Abby’s bird eats right out of her hand, so close. Why can’t mine be closer?

Some believe my sister never got over our mother’s death. There is no getting over death. Maybe Roman Catholic doctrine calls it purgatory—a solitary soul stuck in misery winging its way to God’s grace. Others may say the only way out is through. But I wonder instead about those geese, those ranging travelers, a skein lifted in flight across a sloping landscape, heeding somehow an ancient instinct. They, too, in their own peculiar way, are headed home.

Author Laurie Clark is a third-year MFA candidate in creative nonfiction at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. Her work has recently been nominated for AWP’s Intro Journals Projects Awards. In 2024, the North Carolina Writers’ Network awarded her 2nd Prize in the Rose Post CNF competition. She has taught English for over twenty years at various independent schools across the nation. At UNCW, she instructed creative writing and served as both a staff member at Lookout Books and an editorial assistant for Chautauqua Magazine. You can find her essays in Middlebury Magazine and The Doctor TJ Eckleburg Review, and follow her on Instagram @lalaleighclark.

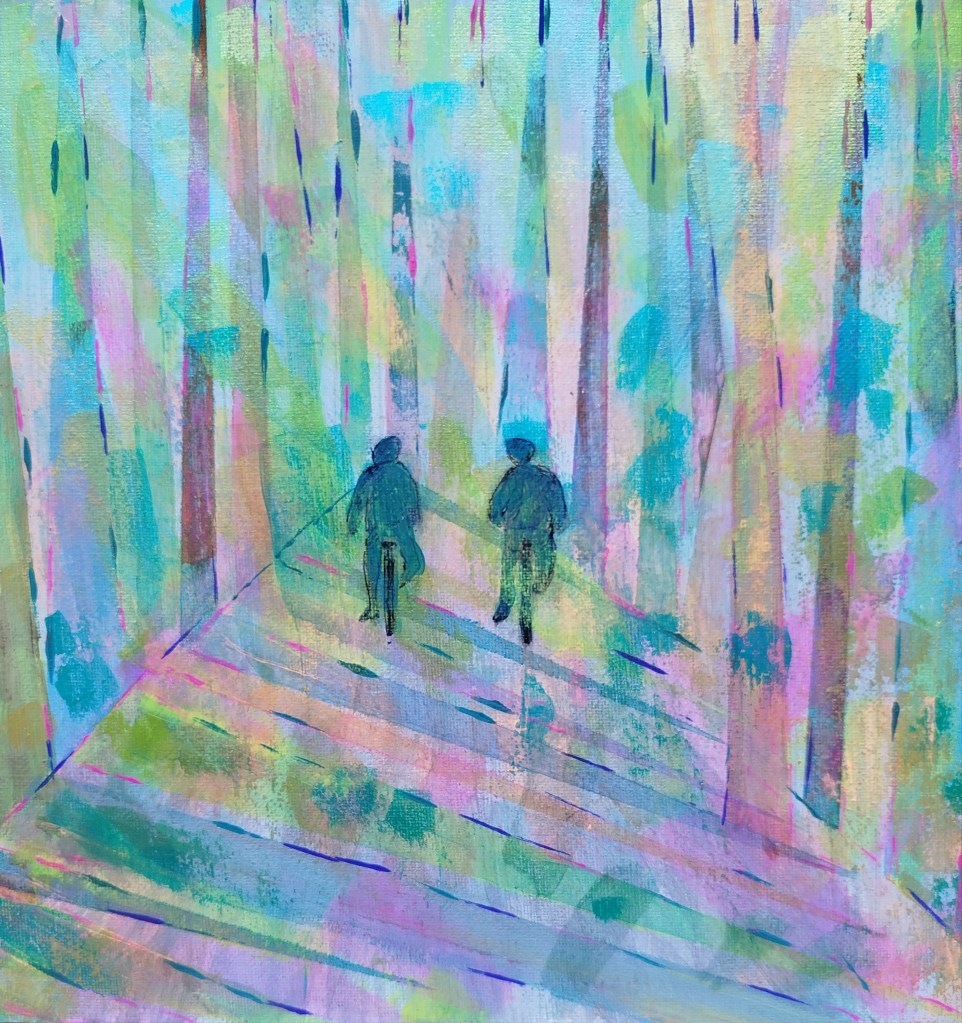

Artist Nuala McEvoy is an artist of English/Irish origin. She started submitting her artwork to literary magazines in 2024, and her art now appears or will appear in around fifty reviews as features or as cover art. She currently has an exhibition of 40 pieces in Cavendish Venues, London.