by Whitney Schmidt

Hope Is the Thing with Seeds

Under my heart a vast apple tree grows wild—sprawling crook-limbed, teeming with green, tough and stout from trunk to twig. She fights for years to breach our back yard, splittingfence posts, rooting under the neat neighbor’s side to the havoc of ours, where grubby tangles of mint and clumps of weeds slouch between anthills and snake holes in cracked dirt.

Here, a few faded daylilies throw back their heads like mute nestlings. The last of the rawboned rosebushes force buds pinched as chapped lips suckling sunlight. Near the kitchen: a naked strip of upturned earth where my mother’s abrupt fantasy of a garden beautiful and bountiful with cruciferous and marrow has gone belly-up in the heat without a single sprout. By the back door: a desiccated history of houseplants cast out to fend for themselves—all bones and dry veins—crispy ferns, withered vines that failed to climb the brick, bodies bowed to callous red clay.

Across the fence liesparadise—lousy with lush leaves, tiger lilies, fountain grass, silvery evergreens. Still, the tree reaches into our world, as if she can sense beyond our dusty Bermuda grass and spikes of wild onion, beneath the creeping red clover, some primal dream of belonging, some promise in the scrappy weeds hell-bent enough to survive our treeless back yard in Oklahoma’s August oven.

Never a sheltered seedling in a storm-free nursery, she’s no quitter—every inch her own and hard won. When even swallows seek shade, she eats the sky, leaves curved like cupped hands catching light.

My mother hates that tree. Orders limbs chopped, stems shoved away, fence pickets fixed. Still the tree pushes back, wanting more—no respect for board or blade, determined to be an apple tree for my family, too. She grows sideways and up as my parents chop, branching at every cut, building a roof farther than we can reach, the face she turns to us pitted and trenched, a silent battleground, war wounds etched in bark.

Whose tree is she, anyway? No one seems to want the trouble. No one claims the fruit but the birds who pierce the skin and leave the bodies behind.

And me. Under the apple tree grows my empty belly, that hungry monster I carry with me always, even when I am full. At seven, I learn to scale the fence, to ignore splinters, to reach. But the apples are too far, and I fall many times to unforgiving dirt. I learn to watch and wait for the wind to work her magical release.

Some drop in June, small fists that punch the ground, green-gold bodies with thick, intractable hides. You don’t want those, my mother tells me. Don’t come crying when they make you sick. She sends Dad to get rid of them. He teaches us how to whip them over the back fence hard enough to cross the alley and smack the concrete side of the supermarket. They burst like plump skulls. He tells us they are crabs. Good for nothing.

But I know they are real, honest apples, somewhere between granny and golden, and fit right in my palm as if shaped just for me.

I learn to hide what falls.

One midsummer, I am tall enough to stretch from the fence and reach the fruit. I gather my harvest in secret, find corners out of sight and sound, and crouch low, feasting on their crisp, sour hearts. I do not share. I stuff myself with bitter apples but never, not once, get sick.

Once, I am caught and my mother sends me to her closet for Dad’s leather belt. I am not surprised. It is not the first or last time I am punished for eating wrong foods at wrong times.

One year, I catch my little brother sneaking apples to his room, too. We learn to share secrets.

When I am eleven, I dream of splitting an apple like a geode to the trove: glittering oval garnets in firm, pale flesh. I learn to bake the cores on a flat stone, shake out the seeds, tiny auburn gems, hide them in cold corners. Every fall I bury dozens. With each seed I tuck a splinter of hope. Every spring I find nothing.

When I am fifteen, we move across town and leave the apple tree behind, still reaching. I wonder whether the next family will let her loose.

Author Whitney Schmidt is a teacher, writer, and amateur lepidopterist with a passion for poetry and pollinators. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Harbinger, So to Speak, Wingless Dreamer, and Wild Roof Journal. She lives near Tulsa with her partner, two pit-mix pups, and various moth and butterfly guests.

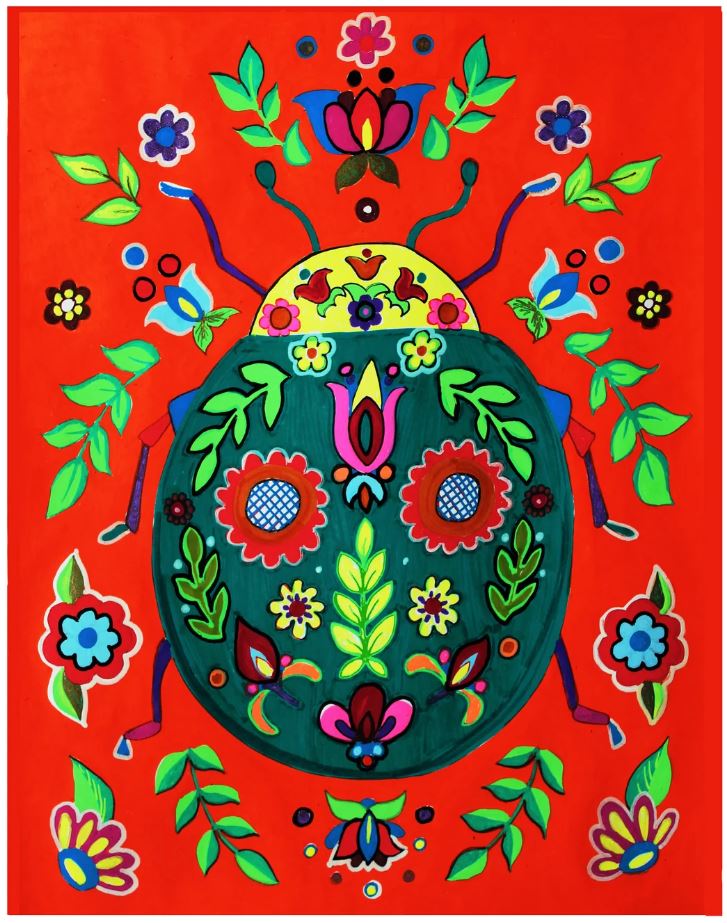

Artist Margo Moore was born and raised in Poland and lives in New York City community her home. Specializing in both abstract and figurative work, her portfolio includes portraits, paintings, and abstract drawings. Her artistic journey has taken her to numerous international and US-based exhibitions, including the Netherlands, Poland, various shows in Chicago, Florida, and NYC. Currently, Margo’s smaller works can be seen on display at NYPL’s 440 Gallery in Brooklyn, NY and at the United Palace in Harlem.