by A. Molotkov

Transfusion

1. Sarah

The smell of rot is so pervasive it adheres to the inside of my nose and mouth. I force myself to ignore it.

Impossible.

The horizon is interrupted by the red glow of forest fires. The other woman’s face, too, is tinted red. She’s walked with me for a while. A rabid lightning strikes, and a second or two later, the silence is ripped apart by thunder. Will it start raining again? As it is, the water level keeps rising, imperceptibly. Could be a failing levee or, simply, these five months of rain. The flood is up to my hip, but it’s already reached the woman’s waist, and she moves with difficulty. I ache at the thought of her useless suffering.

No one else in sight. No buildings, no structures to climb on. The hills we’re trying to reach loom miles ahead, and time is not on our side. I’d love to believe that something will interfere with our drowning.

“It might be shallower as we get closer to the hills.” I don’t really know, but I desperately want to communicate, to exchange a fraction of warmth, or at least some optimism.

The other woman’s elongated face is framed by dirty clumps of blonde hair. Her expression doesn’t change, nor does she give any sign that she’s heard me. Her nondescript dark blue sweatshirt is soaked.

“What happened to you?” I try again.

Her eyes slowly move as her neck turns, like an automaton’s. She makes eye contact, but her stare conveys neither an answer nor another question. Yet, her eyes are not empty; I can feel a vast, meaningful life behind them. She will not reveal it; she’s in a different world.

Too many strangers these days are unwilling or unable to share information. I keep slogging. Water all around us; not a single tree in sight, only the fragile mosaic of shrubs sticking their naïve top branches out of the water. The flood has turned what used to be a vast field into a stream with a layer of mud at the bottom. The mud clings to my heavy military boots, each step a challenge. My ankles burn with lactic acid, my knees hurt from days of walking. The woman must be even worse off; when I turn my head, I see a reflection of her effort in her crinkled forehead, her intense blue eyes staring ahead.

There must be survivors elsewhere. The wealthy always find a way; humanity will continue, in reduced numbers. It feels strange to think in such abstract terms about humanity as a whole, but my daughter is the only human I still care about, and she’s thousands of miles away. When I was drafted, they deployed me as far from home as possible. Then the disasters came.

Lung cancer took her other mother three years ago. We didn’t have the insurance to cover immunotherapy. Lung cancer is not unlike drowning: as the tumors grow, they reduce lung capacity and build their own blood supply lines that conflict with oxygen delivery.

The water keeps rising, but the distance between us and the hills ahead doesn’t seem to shrink. The woman remains close, her chest cutting through the water to my left.

“Can you swim?” A bright, melodic voice.

So, she is capable of communication. I’m pleased, and I feel a light smile on my lips, entirely inappropriate for the circumstances.

“I wish.” I remember my youth in Arizona. The rains were most of the water we got, but nothing like these new unending rains. “No one ever taught me. I’ve never lived around water. You?”

“Me neither.”

*

Has it been twenty minutes? Thirty? An hour? The water has reached my shoulders. For the first time, it fills me with panic. I feel as if I might choke, and as I struggle to breathe, I force myself to count to ten in my mind until the fear subsides. The water washes small particles down my clothes. They creeped me out at first, but I no longer care. Bugs and carcasses of dead rodents float around us. I can’t see the mud underneath, just the grayish brown stew. The undercurrents threaten to trip me up, the water’s resistance against every step reminds me how tired all of my muscles are.

I look to the woman on my left, who must work so much harder than I. Only her head and the top of her neck are visible. Tears trickle down from her eyes and fall into the water.

“Come on, hold on to my shoulders.” It just comes out.

She stops walking, a series of hesitations in her eyes. “Thank you.” She’s out of breath.

I’m glad she’s accepted. The water may stop rising any minute. Awkwardly, she grabs on to my neck from behind. I can feel the balance shift; she must have let go of the bottom. The grip of her fingers is strong; I use both hands to move them over to my shoulders. As I resume walking, the water clinging to so much of my body makes every sensation urgent, like an eclectic charge.

“Thank you,” she repeats. “You can still make it. You’re strong.” Her hands on my shoulders remind me of my daughter’s hands from the earlier, happier years. “Do you have children?” The woman must be reading my thoughts.

“A daughter. She’s living with her aunt.” My voice shakes. “I was arrested, then drafted. By mistake, you see. But anyway, we got separated. But my sister…she has a drug problem. Had. Oh, I don’t know. I’m worried about them.”

“My daughter’s in jail. Political charges.”

“I’m sorry.” I want to tell the woman that I appreciate her for not letting me go through this alone, but it’s an awkward thing to say. “What’s your name?”

“Latisha.”

“I’m Sarah.”

“Nice to meet you,” we say in one voice, and then laugh at the ridiculous sadness of running into each other under these circumstances.

“If you make it out and I don’t, there’s something you must do for me,” I say.

“Anything.”

*

Water is up to my mouth. It’s too late for us. I tilt my chin up to breathe; the brown liquid vigorously resists my every move. The turbulence at the bottom gnaws at my feet, reminding me that any second, I might lose my balance. I pay attention and plant myself firmly with one foot before I set the other forward for the next step. But we still have at least half a mile to go. And if the water keeps rising…

I lose my balance.

The liquid world around me, tumbling, tumbling. But it’s the two of us who tumble, Latisha and I. The water in my face, nose, mouth. Its foul taste. I panic, grab on to her waist, push her up in the direction where the sky is supposed to be. And then, I’m being dragged away by the current, facing the sky, facing the water, which fills my mouth and nose.

2. Latisha

I open my eyes to a concerned face hovering above me: tanned, with deep wrinkles across the forehead. She must be in her fifties. White surgical cap. White ceiling with bright lights. I raise my head. A blue inflatable cot under me. The smell of rot has not abated.

“Latisha? Can you hear me?” How does she know my name? “Don’t worry. We scanned your DNA record.”

“What happened? The last thing I remember is water all around me.”

“They drained it.”

“Drained?”

“Yep. They built an underground reservoir under this valley seventy-two years ago.”

“Why didn’t they drain it earlier?” I’m disoriented.

“The right-wing coalition wouldn’t approve it. Because flooding was God’s work, wouldn’t you know it?”

“What?” How much credence should I give to this tale? No one knows anymore how to tell real news from fake. Even a government official might be spreading nonsense. Then it comes back to me, with a surge of panic: Sarah, carrying me until she lost her balance. The water filling my mouth. Her desperate efforts to push me up. “What about the people who didn’t make it out?”

The technician shrugs.

“The tall woman who saved me?” I make eye contact. “Have you seen her?”

“No, I just got here. I’m sorry, but she might have been dragged under.” The technician looks upset about this, a frown on her face. “The draining took a few minutes, you know.”

My heart might collapse. I’ve grown attached to Sarah, even though we spent only two or three hours together. I look around. The field is being cleaned up; technicians are busy dragging away debris. Remnants of water still shimmer in gullies and puddles formed by dust and trash.

“Where is she? Can I see?”

The technician nods. “Come with me.”

These days, simple requests are honored. The only good thing about our times.

She walks me over to a covered area some hundred yards off. A gigantic white tent, like a medical station or a disposal location. The smell of decaying bodies. Something feels dead in me, too. Surely, I should have been the one to end up here, not Sarah. If she were on her own, she would have survived. How to explain that she chose to save me instead of saving herself?

“Sure you want to see her?” The technician asks.

“Yes.”

“Here you go.” She hands me a small respirator and dons hers.

As we enter, the smell is strong. I hurry to pull the rubber thing over my face. A vast space to my left is dedicated to animal carcasses. Mobile crematoria are already deployed. I’ve seen the footage during the earlier flood reports, but it’s strange to observe these devices in my proximity. Flames dance in one of them as it opens to take in another body. A deer? A moose? Human carcasses are eventually burned too, unless claimed by relatives. So few relatives remain.

To my left is a smaller area with two rows of tables. Only six or seven of them are occupied. Most locals perished earlier, when the famine started. Here, surviving until the flood became a tragic luxury. The technician leads me to the second table on my left and tactfully stays to the side.

Sarah’s body is covered with a blue sheet. I pull the top away from her face. Her brown skin is still full of vitality; her heavy eyelids curve with an outward passion as if she might open her eyes and speak. I walk over to her side, reach under the sheet and find her hand. It’s cold as I hold it in my own.

“Thank you, Sarah,” I whisper.

After a minute, I walk over to the technician. “May I have her DNA profile?”

“Was she a relative?” A tear in her eye; she must be thinking about someone she has lost.

“She saved me.”

“Why do you need her profile?”

“Her daughter.” I explain, thinking about my own, lost somewhere in the prison system. Maybe they’ll let her out now? I hope so. But she’s an adult; she doesn’t need me. Not anymore.

*

The small blue house looks unreal; I haven’t seen anything as intact in years. The country must be changing for the better. In the months since my DNA transfusion, my body has been changing too. Growing. I feel as if I’ve been here before. The flowers in the garden smile at the sun. I walk up the blue steps of the porch and ring the doorbell.

I’ll find a way to get along with my new sister. Where is she, anyway? A little girl opens. Four or five. A white dress, a cute, expressive face with brown bangs. Inquisitive green eyes. It’s another chance, for me. I’ll grow to love this face, spend hours staring into these eyes. Years will slide by, touching both our heads.

“Mommy!” The little girl hugs my legs.

“Yes, baby.” I kneel on the blue porch and open my arms.

Author A. Molotkov’s poetry collections are “The Catalog of Broken Things,” “Application of Shadows,” “Synonyms for Silence” and “Future Symptoms”. His novel “A Slight Curve” and his memoir “A Broken Russia Inside Me” are forthcoming; he co-edits The Inflectionist Review. His collection of ten short stories, “Interventions in Blood,” is part of Hawaii Review Issue 91; his prose is represented by Laura Strachan at Strachan Lit. Please visit him at AMolotkov.com

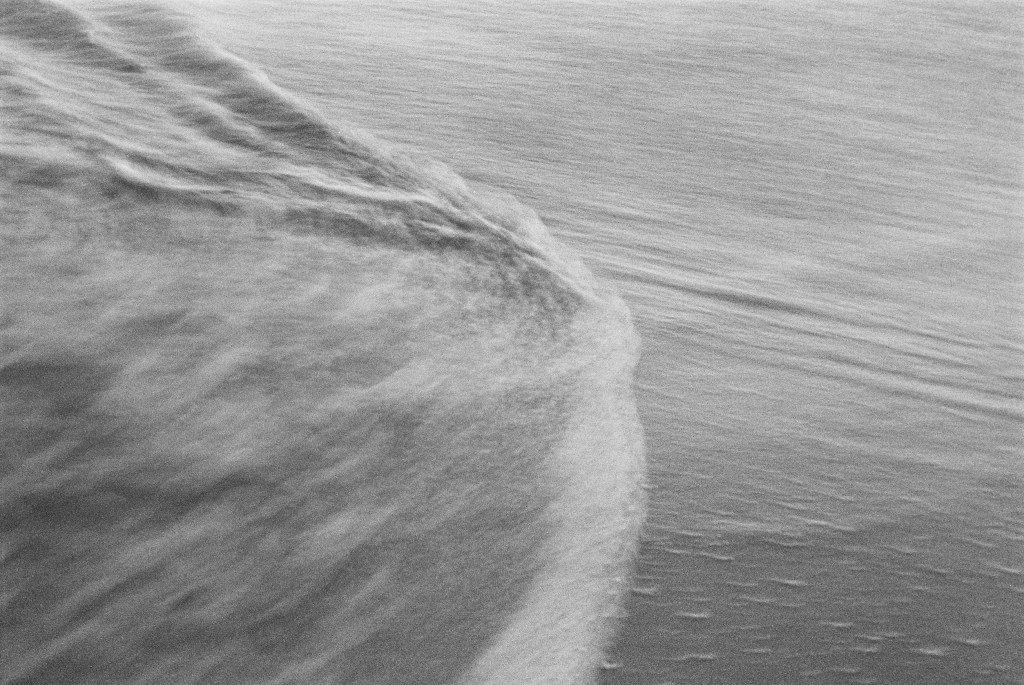

Artist Ian Gonzaga is an artist born and raised in Southern California. He received a BA in Film & Television Studies from Cal State University Fullerton. The majority of his career has been spent living and working in Orange County and Los Angeles. His artwork is deeply influenced and inspired by nature. It is these natural elements and the way in which they interact with philosophy and culture that interest him. He is an explorer of environments, perspectives, and ideas using photographs to express feelings and energies. His work can be found at https://foundwork.art/artists/iangonzaga