by Kris Norbraten

They dragged the doll into the hot shower to get it back to life. Some semblance of life. It wasn’t exactly a doll or wasn’t supposed to be. It was supposed to be something more.

Randi’s bare feet squeaked on the acrylic shower bottom. She’d gotten herself wedged into the stall, no bigger than a coffin. Water trickled on her and the latex doll. Steam filled the bathroom and fogged the mirror.

“Why didn’t you pick up that new shower head?” Randi asked her brother. Theirs had lousy pressure and was unable to charge the doll the way it used to.

“Didn’t make it to the hardware store,” Russel said.

There was time, Randi thought, but he’d spaced it. Or didn’t want to go alone.

She grunted under the weight of the latex body as her brother gently took its hips. The skin slipped out of Russel’s grip, and the doll’s feet squidged out of the shower, onto the bathmat. Russel didn’t even try to catch it, and Randi was left holding the doll by its armpits. Water kept on. The doll’s breasts looked like darkened headlights. The skin had no sheen. Face blank, wig matted.

Russel reached in and shut off the dribble.

They got the doll onto the bathroom floor where it lay like a corpse, sogging out the bathmat with its bulk. Russel wedged himself between the toilet and wall. He probably didn’t notice the toenail clippings along the baseboard, the mildewy stink in the walls. Russel rubbed a speck of dirt off the doll’s shin and wiped it on his jeans.

“Randi?” he said.

She plopped onto the toilet lid with its terry cloth covering, elastic shot. “Yes, dear brother?”

“We’ve got to hit that spot on her neck, or else she won’t charge.”

“Don’t call it a her,” Randi said, “or a she.”

Russel shrugged. “She can’t get this wet.”

He was right, but Randi had bigger stuff to worry about than an over-saturated, oversized Barbie that only somewhat resembled their dead mom. Stuff like the electric bill. And groceries. And her brother’s sanity.

“Hadn’t we better move on?” she said.

Their mother had passed three years ago, when Randi was twenty-one and Russel was sixteen. Randi figured her brother was strong enough to cope and would eventually get over it. Instead, he went online and found an inflatable BioBlo doll. He said they could program it to walk and talk like a real person, and begged Randi, and promised he’d use his portion of the money from their estranged uncle.

Randi hoped the doll would fill a gap until she could find Russel real help. Only when the doll came, and the siblings sliced open the box, and the latex expanded into shape, and Russel saw its potential, he didn’t want real help anymore. To Russel, help had arrived.

Now he was on the bathroom floor with a pathetic, imploring look on his still-baby face. He wasn’t a baby though, not by a long shot. Coming up on twenty. Randi remembered him as a baby, though. She watched over him enough, gagging on the stink of his shitty diapers. They never had enough money to change him as often as they ought, so he always had to sit in his shit way too long. Randi remembered the look of distress on Russel’s little face when she spread him out on a blanket to change him. He had that same look now.

“Don’t worry,” Randi said, “we’ll find a way.”

As soon as Russel cleared out, Randi dragged the doll to the garage, and hoped her brother would forget about it, but knew he wouldn’t.

“What about a solar charger?” Russel—chewing dinner with his mouth open—said.

“How much is it?” Randi asked.

“Ninety bucks.”

“I don’t have a fat hundo lying around, do you?”

Russel scratched his head with his fork hand, depositing a chunk of potato in his hair. He never noticed globs of toothpaste or dangling strings, forever picked his zits and scabs. His eyes lit, and he waved his fork in the air. “How about the kettle?”

Randi was willing to try. Anything for her baby brother.

The kettle got way hotter than the shower, even without a powerful stream. The siblings headed to the garage, then Russel rushed back for a robe and slippers. In less than a minute he returned and crouched in the garage doorway to collect a dropped slipper. Light from the evening sun haloed Russel so that, to Randi, he had the appearance of a fetal bird—all slick feathers and scrunched-up wings—folded inside an egg. He’s never even tried to crack that egg, Randi thought.

Russel clomped in and set the robe and slippers on the workbench.

“Hold or pour?” Randi asked.

“Hold.” Russel straddled the damp doll, arranged in Grandad’s old chair, then scooped the thing by its armpits and hoisted it to its feet.

Randi took the steaming kettle and climbed onto the chair where she perched over the doll’s head. She wondered what would happen if she yanked a handful of wig and wrenched the head backwards and poured the whole scalding pitcher onto its dumb, blank face. Maybe the skin would melt and the eyes would pop and this whole damn thing would be over with.

Boiling water streamed into the back of the neck at the C7 spinal opening, just like the manual instructed. Most of it got into the portal; only a little dribbled down the doll’s back, into her buttcrack. Randi wondered why the hell they had to make it so real.

She stepped off the chair, unsure she’d given the thing enough water to make a difference. They used to let the shower blast into the portal for a full ten minutes. Russel struggled under the weight of the doll, his rubber boots slipping on the slick garage floor.

“Drop it, would you?” Randi said.

As Russel lowered the doll into Grandad’s chair, his wide stance slipped wider, and he wound up halfway to the splits. Randi set the kettle on its base and got her brother up.

“My pants nearly ripped!” Russel said.

His smile was so innocent that Randi couldn’t help but laugh. There was so much hope plastered on her little brother’s face that she almost felt compelled to hope for something, too.

The siblings waited. Randi leaned against the workbench and watched the runoff pool into an oily rainbow. She couldn’t see the doll’s face and didn’t want to. It didn’t look like her mom. It never had, even fully charged. Powered down, it was uglier than their mother had been flat on the morgue table. Randi wanted to shake her brother and scream, Why? Why are we doing this? She’d hated the doll when it first arrived, and she hated it now.

Randi unplugged the kettle and said, “I’ll save my tips, all right?” Through the doorway, beyond her, across the backyard, past the trees and upwards, the sky was a deep, dark blue. Randi glanced back. “You coming? I got Oreos, the knockoffs, but still.”

“Gimme a sec,” Russel said.

Randi knew nothing could distract her brother from what he wanted most, and she couldn’t bear to witness the letdown, so she left the garage. When she reached the house, there was a sound like a fox—or a tangle of foxes—screeching and laughing. Unsettling. Wrong. Randi set down the kettle and returned to the garage. The figure in the chair wasn’t really a doll anymore. It was animate. Not alive but enlivened.

Randi watched the whole thing happen. She listened to the whole horrible thing.

Russel’s body was limp with relief as he stood in front of Grandad’s chair. He didn’t notice his sister in the doorway.

“Let’s get you dressed,” he said in his most tender voice.

The doll bent at the waist and rested its head on Russel’s belly. He took the robe from the back of the chair and gently eased in the doll’s arms. He wiggled the slippers onto its feet.

“Come on now,” Russel said, and helped the doll to stand.

“Hello,” the doll said.

“Hi, Mama,” Russel said.

“What day?” it asked.

“Tuesday. I’m pretty sure it’s Tuesday.”

The doll turned its head and blinked. “Where?”

“We’re in the garage. You’re in Grandad’s chair.”

“Garage,” it said. The thing even nodded, as if it understood. “You are?”

“Your son, Russel.”

“Son, Russel,” the doll repeated.

Russel braced its elbows, to help it take a step.

“You can do it, Mama,” he said.

But instead of moving forward, the doll bowed its head. There was an unsteady moment, then it slipped out of Russel’s grasp and collapsed onto the chair. The legs bent at odd angles and the breasts poked out of the robe.

“Oh, God,” Russel said, reaching to pull the robe shut. He crouched and extended the legs, then arranged the slippers so they’d stay put. It was too sad to see. Randi turned for the house.

Weeks passed, and Randi still hadn’t set aside enough for the solar charger, and Russel didn’t bring home squat from the lumberyard. If only he’d stand up for himself, but he didn’t know how. It was like a part of her brother’s brain was missing, or the window for that kind of lesson had long shut. So the doll sat dormant in the garage.

Randi acted like she didn’t notice when Russel snuck a visit, but she took note of everything her brother did. That was her job. Her mother used to say, Keep an eye on him while I’m gone. Well, her mother was gone forever, so Randi’s eye was always on Russel.

On Friday night, Randi tended bar. Duncan from the lumberyard braced an elbow on the sticky surface, ordered a round of Natty Light, and said, “That little brother of yours.”

Back in high school Randi had learned not to take anyone’s bait regarding her junior high brother. She set Duncan’s pint glasses on the bar and opened her hand for payment.

“He talks about that mama of yours an awful lot,” Duncan said as he handed over his card.

“Yep.” Randi slid Duncan’s card in the bar’s metal file box.

Duncan got wasted with a table full of lumberyard guys. Randi heard him holler, “I caught that crazy little fucker sucking his thumb in the john!” Of course, he was referring to Russel.

Everyone laughed. Stupid trucker hats stained with forehead grease. Beer foam frosting their scraggly mustaches. They slapped the gummy tabletops. Boot soles skidded off chair rungs. The jukebox stalled, flipped discs, and launched into Van Halen.

Past midnight, when Randi got home, she stalked into Russel’s room and flicked on the light, but her brother didn’t stir. She pinged him with a wad of socks, and when that didn’t work, she pounded him with a pillow.

Russel sat up and rubbed his eyes. “What?”

God, he looked like a child.

“You can’t go around doing stupid shit at work,” Randi said.

“I’m trying.”

“Well, try harder.” Randi flicked off the light and left.

The next morning over breakfast, Randi said, “Keep your thumb out of your mouth today, okay?” She scraped her brother’s eggs into the trash before he could finish.

The barstool squeaked as Russel leaned forward to grab his favorite coffee mug, the one with cartoon cats. He said, “Are we getting that solar thing?”

“I’m strapped right now.” Randi watched as her brother’s hands began to twitch. He gripped his mug harder, eyeing it, probably wondering if he could take a bite out of the smooth porcelain in order to keep his stupid thumb out of his mouth. “If you save up, I’ll chip in twenty bucks,” Randi said.

“I don’t have seventy dollars,” Russel said.

He was doing his best not to whine, Randi could see that, and she didn’t have the heart to tell him he’d need another ten to cover tax and shipping. He got paid every other week, so even if he saved twenty dollars a paycheck, it would take two months or more.

“Try Facebook Marketplace,” Randi said. She slid the mug out of her brother’s hands, poured him a cup of coffee, and gave it back.

Russel’s palms eased against the porcelain. The cats looked sweetly up at him as he raised the mug to his lips. He didn’t want to bite the mug anymore, and he decided he’d do his very best at work not to put his fingers—and definitely not his thumb—in his mouth, especially if anyone else was looking.

Russel clicked around Facebook Marketplace, but instead of going to electronics, he went to women’s clothing to look at the dress. Not just any dress. His mother’s dress, from the estate sale Randi held the week after Mama’s funeral.

The dress was black and shiny with a low V-neck trimmed in silver beading. Ritzy was the word that came to Russel’s mind when he, as a little boy, had seen his mother in it.

It was only thirty dollars, not as much as the solar charger, and Russel could pick it up himself. He’d saved nearly ten dollars in loose change in the Mason jar on his dresser, and Randi had already promised him twenty.

A man answered the door. Russel hadn’t expected that. The man looked like he probably hadn’t expected Russel, either. They both wore flannel shirts and jeans, work boots and trucker hats. Real fine looking men, his mother would have said.

“How about a twenty?” Russel offered the bill his sister had provided. The man draped the dress over his arm and eyed the change jar. “That dress was my mama’s,” Russel added.

The man’s expression softened. “Twenty’ll do,” he said, and accepted the bill.

Russel fingered the fabric as he walked down the driveway. He lifted the dress and sniffed, but it didn’t smell like Mama, more like cigars and Air Wicks.

Russel hung the dress in the back of his closet. Randi didn’t need to know.

On the sofa, in front of the TV, Russel thought about shoes. What did Mama wear? Silver or black? Maybe red. He couldn’t remember.

Russel went to Goodwill during lunch the next day. He chose a pair of black heels with barely any wear and paid with four dollars in loose change. A beaded purse cost him two more.

Saturday, while Randi was working the lunch shift, Russel opened his closet and placed the outfit on his bed. “Earrings,” he sighed. Clip-ons would have been perfect.

Russel poked his head into the garage.

“I got you something,” he said in a sing-song voice.

Mama always liked surprises. He set the outfit on the workbench and came around the chair. Russel stared down. The doll’s robe had slid off one shoulder. She’d slumped more deeply into Grandad’s chair, and her face was drawn. Russel nudged her shin with his boot. The flesh gave way to the firm steel toe. The skin didn’t bounce back like it should. Russel frowned at the divot.

He hesitated, a heavy glob rising inside him. The dress was so pretty, so perfect.

It only took a moment to decide. Russel hoisted his leg and dropped his lugged boot onto Mama’s knee. The joint bent backwards into the chair, but there was no snap or crack, only mushy softness. The globby thing inside Russel’s chest turned knotty and gross and traveled up his throat and out his nose, which he wiped on his flannel cuff.

“Aren’t you going to say something?” he asked.

Mama was silent.

“The shower doesn’t work and we can’t afford that stupid solar thing,” he said.

She said nothing.

He’d never gotten to see everything she could do. Randi didn’t even read the whole instruction manual. They’d never gotten a full charge, so only half the vocabulary words got into her brain, or whatever it was. Mama needed more software, but they could barely afford her as she was.

Russel leaned so close he could see the gummy pores in Mama’s nose, her fading blush and smudged mascara. He whispered, “Don’t you want to see what I got you?”

She stared back with empty glass eyes.

Russel pulled the dress from the bench. The material snagged on the wood corner. He wrestled the robe out from under her heavy body. Then, propping her against his thighs, he began to dress her. The garment popped over her head, onto her shoulders. Russel got one arm through a sleeve but couldn’t get the other. This wasn’t what he’d imagined while he stood on that man’s porch or picking out shoes at Goodwill. He forced the arm a second time, and the dress ripped.

This Mama was too large, much larger than Russel’s real Mama. His real Mama was muscular, snappy as a whip. This one was flabby and soft with a big belly and thick ankles and a crease in her shin. Probably from that goddamned shower. Russel inched off the dress and set it on the bench with the shoes and purse.

Then he couldn’t stop himself.

He wrapped his arms around the doll, heaved it over his shoulder, and threw it down.

Panting, he stood over the thing. “You make me sick,” he said.

Russel stomped the doll’s belly. He imagined lungs collapsing, stomach ripping, organs going to pieces. But then he laughed and said, “You don’t have any organs.”

He tore off the wig and threw it across the room. He pulled an arm until he felt it disjoin under the skin. Then he took out his pocketknife and began to stab. He shut his eyes and plunged the blade twenty times, fifty, maybe more.

“I hate you, I fucking hate you,” he said. Snot and drool flowed.

He opened his eyes, half-expecting a pool of blood and guts, but there was only a mess of foam latex and wire. Panting and sweating, he gripped his knife harder. Starting at the doll’s neck, he sliced upwards until the face was off.

Only the eyes remained. Dark blue spheres like marbles. Russel gouged them out with the tip of his knife. He stuck the blue beads in his mouth and rolled them around until he had enough spit, then he swallowed, knowing he’d shit them out later.

The pile lay on the floor, and Russel collapsed into Grandad’s chair. He closed his knife and slid it into his pocket. He dragged his cuff across his nose. When he quit shaking, he stood, collected his mother’s outfit, and returned to the house. He sat with a needle and thread and repaired the rip, just as his real mother had taught him when he was young. The job wasn’t perfect, but it was done.

He went into Mama’s bathroom. Nobody had been in there since she’d died. Brown water shuddered out the shower head, then eventually turned clear. Russel undressed and stepped into the stream. He washed his hair with the shampoo his mother had left behind. He scrubbed under his arms and between his legs with a sliver of soap. Dirty water ran down the drain.

The bathroom filled with muggy air. No towels, Russel went dripping into his mother’s room. The mattress was bare; the closet was empty; dusty curtains hung from their rods. The only piece of furniture other than the bed was a wardrobe with an ornate top and a mirrored front, out of place in the broken-down house. Russel inspected his scrawny reflection. He thought he should look older now that so much time had passed, but he also felt like no time had passed at all, like Mama had died only yesterday, which made time hard to understand, and made it hard to grow up.

He took the dress from the bed and pulled it over his head. It snagged on his damp skin before settling into place. Russel didn’t look like Mama, not completely. He only wanted to see something like his mother again.

He wedged his feet into the shoes, clasped the purse in both hands, and checked his reflection. If he squinted, he could almost see Mama pacing the kitchen, munching on a pickle, waiting for a date to pick her up. He better show up, he won’t want to miss this! She insisted on turquoise mascara when Randi said black looked better. Mama styled her hair like Jill in Charlie’s Angels. Wings, she said, so I can fly.

Russel sat on the end of the bed. He set the purse to the side and pried off the shoes. He didn’t want to wear the dress anymore but didn’t want to put on his dirty clothes, either. When he stood to leave the room, Randi was in the doorway.

“Aren’t you supposed to be at work?” he asked, wishing he had a towel. Even naked would be better than this. The space between the siblings felt bigger in this room. The bed might as well have been a life raft tossing in the ocean.

“The bar was dead,” Randi said. She wasn’t sure whether to join her brother or leave him alone. She spotted the purse and said, “You alright?”

Russel nodded. Wet hair hung in his face.

“I thought we got rid of that,” Randi said, referring to the dress.

“I just needed something.”

“Is it the same one?”

Russel nodded again.

“It fits you,” Randi said. She was inclined to make a joke, about what a cute girl her brother made, but figured the timing was bad.

“I used your money,” Russel blurted. Then he got up and rushed past Randi, down the hall to his room.

Quesadillas were the usual Friday meal before Randi left for her shift. The TV played on mute. Russel sat, ripping a grocery store ad into strips.

“I’m not getting that solar thing,” he said.

Randi flipped a tortilla in the smoking pan. “I know, brother.”

“I’ll pay you back that twenty.”

Randi slid a quesadilla onto her brother’s plate. “I know,” she said. Russel’s intentions were good, even though they never panned out.

“There’s something I’ve got to do tonight,” Russel said. “Wanna help?”

Randi gave her brother a look that said, Of course I do, dummy. She took a bite of quesadilla, pulling it so the cheese stretched a mile, which made her brother smile.

Randi returned from work past midnight and backed up the truck to the garage. Russel opened the tailgate and the siblings loaded the busted remains of the doll and covered it with a tarp. Randi didn’t ask Russel what he’d done, or why.

They drove to the old K-Mart where, as kids, their mother had bought their clothes and school supplies. Behind the store, in a rusty dumpster, they started a fire with lighter fluid and newspaper, feeding the blaze with junk mail and particle board. They told stories, anything they could remember about their mother. One about their old cat, Booger, who dragged dead lizards into the house, and one about the time Mama got up in front of the entire church congregation to defend her dating life. The siblings laughed until their cheeks ached. Russel’s eyes stung with smoke and sadness.

The dumpster roared with flame; the fire warmed his face. Randi tossed back the truck’s tarp, exposing the contorted mess of doll-mother. Without words, and taking turns, the siblings heaved clumps of latex limb and torso into the blazing bin. Russel climbed into the truck and shuffled pieces to the edge so Randi could reach them. The last piece hung over the dumpster’s lip.

“All yours,” she said.

Russel jumped down and, with a swift karate kick, knocked the last strip of latex into the fire. He stood at the dumpster-side, flames licking metal, smoke billowing into his face, until the doll was completely devoured and embers changed from orange to black.

“Good?” Randi said.

Russel nodded, though he didn’t know what good felt like, or where to locate it inside his body, or what good could look like moving forward. But he knew something was over, and that was good enough until he shit out the blue marbles the next morning and he could see what came next.

The siblings climbed into the cab and drove away from the smoldering dumpster. The ride home was quiet until Russel said, “I looked pretty good in that dress, yeah?”

“Cute as a button,” Randi said, and punched her brother in the leg.

Russel popped open the glove box and removed the beaded purse. Inside was a folded bill, which he handed to his sister. With the money they could save, maybe they’d redo the bathroom or build out the garage. Maybe they’d tear the whole place down and start fresh.

The house was dark when they returned. Moths gathered when Randi flicked on the back porch light. When she stepped into the kitchen, and Russel followed close behind, and they turned on the kitchen light, then the living room one, they found their mother there.

She was in the calico curtains hanging over the kitchen sink. Stuck to the fridge with the National Park magnets, places they’d never been and would probably never go. Their mother was mixed in the yellow canisters with the flour, sugar, and coffee, and slotted into the utensil drawer with can openers and spoons. She was stacked in the game cabinet, hanging with the winter coats, and scattered in the pile of mail on the breakfast bar. Their mother was perched on the ends of their beds when the siblings went to sleep at night and there when they woke each morning. Mama was everywhere.

Randi and Russel searched. They found each other’s hands and held on.

Author Kris Norbraten, originally from the NASA community in Houston, Texas, received a BA in English Literature from Baylor University, followed by a Masters of Theology. She now lives and writes in Colorado, and her fiction appears in the Spring 2023 issue of Two Hawks Quarterly.

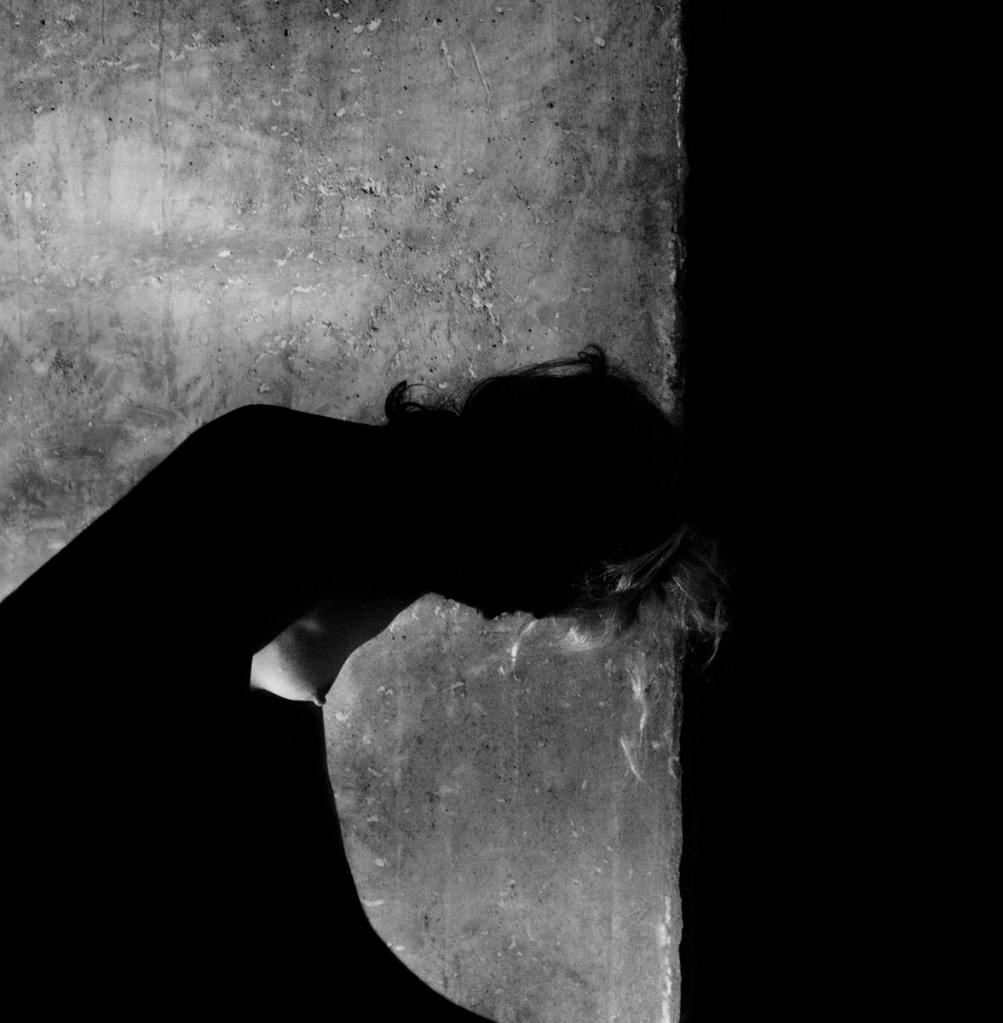

Artist Simon Beraud lives and works between Paris, Brussels and Tel Aviv. His work revolves around questions intrinsic to human existence: identity, roots and uprooting, borders, love. and solitude, memory… Through his images, he invites the viewer to find connections with these questions that drive him. More broadly, he is interested in the evolution of our perceptions and of a collective memory: in the impact of the environment on the psyche and of the psyche on the environment.