by Tali Rose West

Marlboros at Sunset

I’ve started smoking again. Not a whole lot—I’m not a chain smoker or anything—but I like to have a reason to stand on my balcony overlooking the apartment pool and watch the sky. There’s this moment each day when the sun’s setting, just a second before the horrible florescent light on the building across from me seers on, and I try to be on the patio for it every day. I lean my elbows on the railing, a Marlboro dangling between my fingers, and wait for the pink to slip over rooftops and power lines, all of it laced with purple and orange, until, for just a heartbeat of a second, everything is glowing in the wet Florida heat. And then the florescent light, like a shot to the head, and I take another drag and close my eyes.

Johnny smoked. And whatever he did, he did all the way. So it got to be a problem, the smoking, him out on the porch hacking like an old man, that stale, spent smell always on his skin and in his clothes. But there was a time, when he first picked it up, that it was just an every now and again thing.

Back then, when we lived in Wyoming, I loved to smoke on our canoe: a green Expedition we’d bought at a pawn shop. The summer after we got married, we drove the two hours to Casper just about every weekend, the little green boat strapped to our rusted Jeep Wrangler and the windows rolled down, blasting Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, Marty Robbins –always lots of Marty. Those were good drives, starting out early when the air was still cold, the steam rising off our coffee. Sometimes we’d talk, but mostly we were simply together, Johnny driving, my hand on his thigh, his in my curls or cupping the back of my neck.

On his twenty-second birthday – oh, we were so young – I pounced on him in bed before the first light of dawn and hollered, “Happy birthday, happy birthday, get up, let’s go, we’re catching a fish dinner tonight!”

“Turn the light off,” he groaned. He tried to burrow deeper into the blankets, but I twisted up in them and pressed my naked chest to his back and my toes to his calves so that he cried, “Damn you, Josie, your feet are ice.”

“I got you the best present ever,” I crooned into his hair.

“Sleep. Sleep’s always the best present.”

“This one’s even better.”

He rolled over and cradled me against his side. “Go away.” He kissed my forehead. “Let me sleep.” He nibbled my ear.

“You’re going to love it!” I leapt to my feet, the blankets falling around my ankles, and stood over him.

He gazed up at me. “Jolene.”

“Hey, baby.”

“You don’t have any clothes on.”

“Not a lick.”

“As in, you’re naked.”

“Buck.”

“Bare-assed.”

“Au naturel.”

“Come here, baby,” and he reached his arms up for me, grinning.

“You come here!” I jumped to the floor and dashed into the living room, where I’d laid his present on the table: a fishing rod tied up with a bow, and the stocked tackle box his parents had contributed, because like hell could we afford all that. Johnny’d grown up fishing, but his rod had broken a couple years back and since then he’d only gone out when he was home visiting his parents. We all knew how much he missed it.

He wasn’t coming – I swear his clock ran backward in the mornings – so I wrapped myself in his bathrobe and started the kettle for coffee. We’d been so lazy the weekend before we’d left the canoe on top of the Jeep; now all we had to do was lug our cooler of beer and ham sandwiches down the rickety apartment stairs, toss it in the back, and then we could be off across US-287, the sun rising soft and pink over the plains and cattle grazing in fields browning in the dry heat of late July.

“I’m up,” he called.

“Don’t peak,” I cried, and caught him right before he walked into the living room. Covering his eyes with my hands, I led him to the table.

“Okay, open.”

For a minute he just stared at it, a look blooming over his face like this was the best present he’d ever gotten. He opened the tackle box and fingered the weights and lures. He untied the bow from the rod, retied it around my head, and pecked my nose. He mimed casting, then pretended to reel in a big catch. We both laughed.

“Trout dinner it is,” he said.

“So let’s go!” I couldn’t make him move any faster than he wanted to, but I tossed clothes at him, and handed him a thermos of coffee, though when he was ready, I realized I had to pee, and at the very last second, I remembered the sunblock and had to run back inside. Finally we were off. I flipped through our CDs and popped Denver’s Back Home Again into the stereo. Johnny twined his fingers in my hair and sang “Annie’s Song,” his voice still low and gravelly with sleep, me humming along, and we drove out of town like that, like there was nothing better in the world than the two of us, together.

When we got to the river, we unlashed the canoe and hauled it into the water. I sat in the prow and Johnny pushed us out, his mouth going tight when he stepped into the shallows, because the North Platte is frigid even at the height of summer. The boat careened when he catapulted in and we almost hit a rock, but then we were paddling in unison, Johnny still singing under his breath.

The Platte was wide at that stretch, with quiet pools between small rapids, and aspens thick on both sides. It made me think of canoeing the Wekiva with my parents in Florida, where alligators and turtles sunned on lichened rocks and the Spanish moss hung so low from the oaks and cypresses you could almost reach up and touch it. Here the air was dry and clear, the sky an endless blue, and no alligators were lurking below, just brown trout rising for flies. No tourists here, either, not a soul as far as the eye could see. I trailed my hand in the freezing water, making a little wake. Behind me, Johnny popped a can. Then I heard the surge and sigh of a flame as he lit up, and I turned so that I was facing him, and watched him draw the Marlboro to his lips. He held his hand there a moment, and I studied the B tattooed on his forefinger, the L on the middle, U on the knuckle above his ring, and the E on the pinky. He saw me looking and knew I’d ask him why’d he get it? What did it mean? Like I had a thousand times before. He winked and sang, like he always did, “B is for the way I book toward you / L is for the lovely one I see / U is very, very unextraordinary / E is even more than anyone that you adore.” And I burst out laughing like I always did, because I loved how the skin around his eyes wrinkled when he sang with a smile, and I loved the scar parting the scruff on his jaw, and the way he took the cigarette from his mouth and stretched all the way across the canoe, nearly tipping us, to stick it in mine. He cracked another beer and passed that to me, too, and we lifted them heavenward and shouted, “To trout!”

When he steered us toward a boulder, I grabbed a crack in its side and kept us as steady as I could, like I was the trolling motor on a fishing boat. He got serious then, used his teeth to clamp a split shot onto the line, agonized over which lure to use and finally chose a silver spinner. He rested the rod against his shoulder for a second and then cast in a movement as fluid as the river’s current, the line arching up and gracefully curving down to meet the water. He was so beautiful just then that my breath caught in my chest: underneath his thin shirt his muscles showed, lithe and lean, his tan skin glowed in the sunshine, his eyes the color of the rocks that cast shadows over the water.

He whistled when a trout snatched the spinner, and he reeled it in nice and slow as it twisted and bucked. Then it was up and over the side and, holding its writhing body in one hand, he worked the hook from its jaw. A rainbow trout, stippled with black spots and a rosy stripe down its side.

“You want to keep it?” Johnny asked.

It was a good fourteen inches long, and fat, too, so I said, “Of course.”

“Where are we going to put it?” There was an edge in his voice, something that had been happening more and more often, little things stressing him way out of proportion.

“There’s a stringer in the tackle box,” I said. I let go of the rock and we drifted as I scooted across the boat and pulled out the steel cord. I tied it to the rope hanging from the yoke.

“Yeah, but what about when we leave? You didn’t pack a cooler for fish.”

The accusation in his voice made me bristle, and I kept my eyes down, focused on my breathing. A spider skittered across the floor, up the side, and clung to the gunwale.

“We’ll just put them in the cooler I did bring.”

“With the beer?”

Swearing at myself for being so annoyed with him, I forced a grin and said, “You think there’s going to be any beer left?”

“Good point.” He handed me the fish and took up his oar just in time to keep us from hitting a fallen tree.

I ran my fingertips over the slipper scales that glinted in the sunlight and stared into the bulging eyes. They already look hazy, glossed over, like it knew it was going to die and was preparing itself for the end. “It’s beautiful,” I said, and I threaded a clip through its lower lip and dropped it into the water.

We paddled a while then, until we edged against another boulder. I held us steady as Johnny cast and reeled, cast and reeled, until he caught another rainbow, its body shining like tinfoil as it fought across the river and into our boat. Again he handed it to me and I marveled at the strength of its fins, the way its gills fluttered like feathers. I pulled the stringer up and hooked it next to the other. The sun was high overhead and hot enough that I pulled off my shirt. I stretched out—my head on the yoke, my feet dangling over the prow—and watched a solitary hawk wheel across the blue.

“Think he notices us?”

“Everybody notices you, Josie Sue.”

I closed my eyes and smiled. Let the warmth settle over me. Johnny lit another cigarette and kept paddling until we came around a bend in the river where the aspens gave way to rocky shoreline. He jumped into the shallows and shoved the canoe onto the beach, then he grabbed the rod and held it out to me.

“You want a turn?”

“Later,” I said. I flipped around so that my shoulders rested against the prow, my legs over the yoke, and I reached for him. He knelt down and kissed my forehead, my eyelids, the crook of my neck. I hugged him tight, kissed him back, and there was nobody to see, nobody but that hawk, still circling overhead, and Johnny slipped my bikini top over my head, jean shorts over hips, and the sun cascaded brilliant light and heat over my bare breasts, belly, legs. He settled himself over me, gentle as the river, rocking like the canoe, and it was like sitting on the jetties back in Florida as the waves crashed over me, like standing in front of the trains until I could feel the whoosh of squealing brakes, the whistle charging in my ears. It was like, this is it, this is life, and I remember thinking, Johnny, Johnny, it’s all of this, always, with you.

—

I did fish later and caught a brown trout with an underbelly of green. We drank the rest of the beer and paddled back to our car. While Johnny emptied the cans into the trunk, I tied the stringer of fish to a branch hanging in the water. Crouching at the edge of the river, I unhooked the first fish and looked into its gold-rimmed eyes. “Thank you,” I whispered, feeling a little silly, but I hated this part. Growing up, my dad had always done it for me, and I waited for Johnny to come over and slip the fish from my hand, be the one to deal the killing blow, but he was still messing around by the car and I didn’t want to ask. I picked up a rock and smashed the trout on the head. It went limp. I dug through the tackle box for the knife, slit the belly, and cleaned out the entrails.

“Johnny, bring the cooler?” I called.

He set it beside me and I tucked the fish into its bed of ice.

“Want to do the next one?” I asked.

“You’re doing great.”

He sat against a rock and smoked while I cleaned the next two.

“Want one?” He held out the pack of Marlboros as I closed the cooler lid.

I tapped a cigarette from the foil and lit it off Johnny’s. We sat side by side, both leaning against the rock, our exhales mingling and floating sluggishly away on the warm breeze.

“It’s been a while since I had a Lucky Strike. Used to be all I smoked.”

“You married a Marlboro man, baby—new allegiances now,” he said, and I laughed.

When we’d finished off our cancer sticks, we heaved the boat on top of the Jeep and tied it down tight. Driving home I didn’t turn on the radio and Johnny didn’t sing. It was like the music was inside of us, we were so filled up with the bright blue sky and the river between its wide stretching banks, the trout waiting in the cooler, and the way we had loved each other on the floor of our canoe. I grabbed Johnny’s hand and kissed each knuckle, and he played with the hair at the nape of my neck as we flew down the highway, the ratchet straps going wild in the wind.

I was so happy, my heart busting up with it, that I said, “Let’s have a baby.”

Johnny unwound his fingers from my hair and clenched the steering wheel, ten and two. He stared straight ahead, a vein swelling purple along his temple. He was dead quiet, which was bad enough, but the awful thing, the part I can’t really describe, is the way he was just suddenly gone. After being together all day—one flesh, the whole thing—it was like I was suddenly sitting in the car with a person I didn’t know. Someone I couldn’t reach. It had been happening more and more often, but every time it was a total shock, as if I’d been punched in the gut. I sunk against the back of my seat like somebody’d knocked the wind out of me.

“I’m sorry, Johnny,” I said, resting my hand on his arm. “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

“I’m not upset.”

“Annoy you, then.”

“You didn’t annoy me,” he said, but he moved his arm so that my hand fell into my lap.

I tucked my knees under my chin and wrapped my arms around my shins. “I’m sorry, Johnny,” I whispered again, though I didn’t know what I was sorry for. Staring out the windshield at the cattle in the fields and the Wind River Mountains beyond, I prayed I’d stop saying things that made him disappear from me.

Now, years later, this is one of so many memories that’s as hazy as the dying eyes of all those trout. I twist and turn it in my mind, and maybe I’m not remembering quite right, maybe I’ve got something wrong, because that sudden change in Johnny, like he was no longer himself, it just don’t make sense. And what’s crazy is that I’m beginning to realize I’ll probably never make sense of it. That was four years ago, and here I am alone on a balcony in Oviedo, Florida and I take another pull on my Marlboro. The sky is vivid with pink and orange and I’m sure it’s beautiful, but the florescent light glares so bright it’s hard to see. I snub out my cigarette and pad through the apartment and down the concrete stairs, across the grass, and to my car. If I sneak Dad some dip, he’ll wink at me and tell Mom he’s got a hankering to go fishing. We’ll take his old jon out on the lake and maybe then, there on the dark water, maybe I’ll be able to talk about some of this – maybe even figure out a way for it to make a little sense.

I love the drive to my parents’ house, especially in this light, all the trees and neighborhood streets glowing quiet and gold. I stop at the Food Mart and pick up a tin of Copenhagen and another pack of Marlboros, and I hide them both in my purse when I pull up to my parents’ house. It’s been a few weeks since I’ve visited, but they don’t seem surprised when I walk through the back door without knocking and sit down at the kitchen table. They’re in the middle of dinner, and Dad says,

“Leave it to Josie to show up just in time for the food.”

Mom gives him a look, and says to me, “Perfect timing, honey. You don’t eat enough these days.” She gets me a plate and heaps it with spaghetti.

I realize I haven’t really eaten all day, and suddenly I’m famished. I stick a whole meatball in my mouth and wink at Mom.

“Hey Dad, what do you think about taking the boat out?”

“Tonight?”

“Tonight,” I say, and pass him the tobacco under the table.

“What’s that?” Mom asks.

“Nothing,” Dad says, slipping the tin in his back pocket. He looks at me. “Tonight,” he says.

“You want to come, Mom?”

We always invite her, though we don’t really want her, and she always pretends to think about it, though we all know she’d rather stay home.

“I wish I could, but I better take care of these dishes.”

Dad stands. “I’ll get everything ready,” he says. He washes and dries his plate, puts it in the cupboard, and goes into the garage.

I help myself to another serving of spaghetti. Mom watches me eat. She’s wearing an apron over an old cotton dress, and pearls around her neck. The kitchen light makes a halo of her graying hair.

“How are you, honey?” she asks.

I know she’d love to have some big heart to heart, and it would probably do me good, but I say, “I’m fine. Work’s going well. I’m reading a lot.”

“I hope you’re spending enough time with friends.”

“Plenty.”

“And not just Nathan.”

I take a swig of her water and say, “I haven’t seen him in a while.”

“It’s good to have girl friends, a group, not just one person.”

“I get it, Mom.”

“Nothing against Nathan. He’s always been so good to you. . . I just want you to be careful.”

“I’m going to see if Dad needs help.” I stick my plate in the dishwasher. I’m about to walk out the side door, and then I swing back and kiss Mom and the forehead. “Thank you for dinner,” I say, and she squeezes my arm.

Out in the garage, Dad already has the trailer hooked to the truck. “Ready?” he says.

“Ready.”

He slides behind the wheel and I hop into the passenger seat, then say, “Beer?”

“There might be a couple in the fridge.”

I run inside, grab three cans of Yuengling, and jump back into the car.

“Been a minute since we’ve been out,” I say.

“The lake is probably so overrun the fish’ll be jumping in the boat.”

“We’ll show them they can’t run us over.”

I prop my feet on the dashboard. It’s a short drive to the neighborhood lake, where we back the truck down the ramp and drop the boat into the algae and lilies and invasive curlicuing weeds. It’s not quite dark yet, the sky a deep blue and the moon just beginning to rise. We putter toward the middle of the lake, and lanterns wink to life on the docks around us. A dog barks. Dad hands me a rod, then ties a weight and spinner onto the line for me. He picks up the other pole and we cast at the same time. He tucks a plug of tobacco behind his lip. I light a cigarette. We reel, cast, reel. There’s a breeze blowing and the night sounds are loud, the live oaks and reeds teeming with birds and frogs, katydids and crickets. Usually, I miss the silence of Wyoming, but tonight I love the chaos of all this sound, life rising up and billowing out of everything, everywhere. I crack two beers, pass one to Dad. We drink, cast, reel.

“Nothing’s biting,” he says.

“So much for overrun.”

“It’s all these old retired guys out here every morning.”

“You’re going to be one of them before long.” I’m teasing him, but it hits me that he is getting old. His hair has turned mostly white in the last year, and his shoulders have sloped.

He spits black juice into the lake, and then he whistles loud as he hooks a fish and pulls it in. I flip on the flashlight and shine it on a largemouth bass, the silver lure down its throat. Dad holds the gills down with one hand and with the other works the hook out slowly, almost tenderly.

“Want him?” he asks.

I shake my head. He releases him back into the lake, and the ripples close over him. I set my rod down and dangle my feet over the edge. The water is warm.

“Dad?” I say. I tap the cigarette pack, draw out another, and roll it between my fingers without lighting it. “I’m getting kind of lonely, Dad.”

He sets his rod down, too, and he reaches across the length of the boat and takes my hand in his. I can feel the callouses on his palm. He doesn’t say anything, and I don’t either, and we sit like that, holding hands and watching the stars rise, until the mosquitoes are bad enough to chase us back to the truck and through the quiet neighborhood streets to the house, where we stand in the driveway before unloading the boat, Dad with another plug of chew and me with my last cigarette of the night.

Mom opens the back door and when she crosses the yard, the motion light flares on, so bright the grass looks like neon. She steps onto the driveway, the cement buckled and crumbling where the roots of the oak trees have grown up under it. She’s wearing slippers, and she reaches for Dad’s hand. Her eyes narrow on the Marlboro between my teeth and I wait for her usual litany: Why are you always chasing after death, Josie? Why must you spend half your life trying to kill yourself, Josie? But tonight she simply says, “Catch anything?”

We both nod, and Dad says, “We released it, though.”

The florescent light cuts off. It seems much darker than it was before. Mom circles behind me and stands to my right, her hip brushing mine. Dad is on my left. The trees are full of birds calling into the night and I wish I knew their names. A breeze swooshes through the leaves and they join the chorus, too, and somewhere the low hooting of an owl. The air is hot and damp and smells of gardenias. My cigarette goes out. We stand there together watching the sky as if we are expecting something, a meteor shower or maybe a lunar eclipse, the moon going blood dark, the darkness almost a thing you can taste, like when I was a kid and we piled blankets and pillows on the driveway and drank hot cocoa and watched the earth’s shadow cover the moon, while Mom and Dad sang my song to me, Jolene, Jolene, as if I had something to do with the way the sky tinged red. Tonight the moon is a crescent and we can see the stars. Not many, here from our suburban drive, but each one shining bright and true with sweet, soft light. I take a long, deep breath and tuck my cold cigarette into my pocket. Standing here with my parents, I listen to the mosquitoes and crickets and all those birds in the trees, every one of them singing and singing, and maybe to me.

Author Tali Rose West has work published in The Saturday Evening Post, Raleigh Review, Bayou Magazine, Image Journal, Litro, and elsewhere. In addition to writing and freelance editing, she teaches elementary school in the Northwest, where she lives with her husband and pup and an ever-increasing number of houseplants and books.

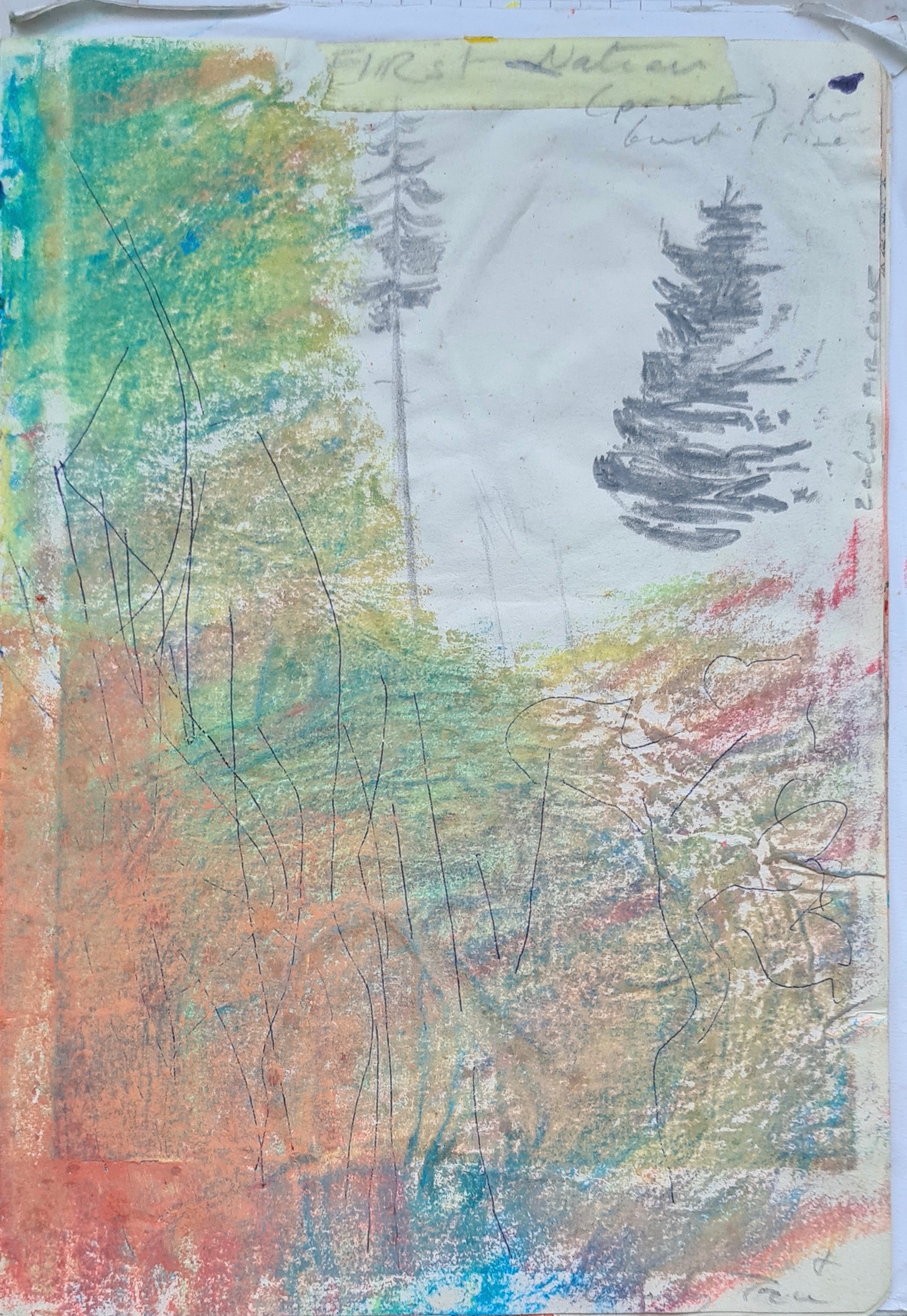

Artist Rowan Kilduff has had pictures appear on nanaoglobal.com; rewilding.org, ecozon@ España, and zestletteraturasostenibile.com, & poems and interviews in Rewilding Earth, Wingspan (Raptor Research Foundation US), Shufpoetry, The Irish Poetry Reading Archive, UCD, Camas Montana. His book, Wind to Space, will be out in 2024 from New Jersey publisher Read Furiously, and he has a book called Fire songs, sky songs, mountain songs (2022) with a foreword by Jack Loeffler (Headed into the wind). His work can be found on Flickr.com.