by Vimla Sriram

A Word Flows Between Us

When the word Heathen barrels past the street and lands at my feet, I already know its intended for me even if it hangs unclaimed suspended like molecules of mist before the averted eyes of the regulars at the transit center.

*

Among the more palatable meaning of Heathen is one further down the dictionary: those that live in the heath, the wilderness.

I think about wilderness. I think about us.

How greedy we are. Leaving nothing out. The stone, a stone, all stones. The hill shaped like a bell. The bell shaped like a hill. The cow with a hump. The one without. The snake. The peacock. The rat. The elephant. The tree at the fork in the road that we tie strings around. The tree that forked the road on which hang our wishes, wisps of colored cloth, fluttering from the branches. The soil. And the ants that walk drunkenly on it after carrying away dots of rice flour from the pattern we make on the threshold of our houses, a new one each day.

*

No one knows the exact number of gods and goddesses in the Hindu pantheon. If my grandmother’s word is as good as your grandmother’s then it would have to be 30000000. That’s more zeroes than I know the place value of without counting the notches in my fingers. I prefer to think we chose our gods based on how many we could fit in our houses. In the corner of our kitchen in Delhi they lived in two cramped shelves, a jumble of images and statues, with pictures occupying the walls – from stamp sized to calendar-sized, black & white to colored, magazine tear-offs to temple -bought and figurines filling up the floor – marble busts, granite symbols, brass trinkets, and bells. A hoarder’s divine paradise. Our weekly chore was to clean the gods without breaking them. While my elder siblings stretched into corners unhooking pictures, wary of darting cockroaches, I sat on the mosaic floor next door with a wet dusting cloth in one hand, a cup of sandalwood paste by my side. The pictures they stacked, I’d pick, wipe, dab a dot of paste for the next in line to top with vermillion powder. This image of Sunday mornings enters my mind each time I think of the afternoon at the transit center – of me sitting cross-legged, carefully wiping glass frames while being happily surrounded by a wonderment of knickknacks perfect for a child’s hands – glacier-smoothed gray Himalayan pebbles, brown bounceable corrugated seeds, dented ping pong ball-sized brass pots with (questionable) Ganges water. Looking up from my writing desk, my eyes rest on the narrow two-inch ledge lining the wall above my laptop on which are displayed tiny inspirations collected over eight years of northwest living: pebbles, white and sparkly, from rivers that I have crossed in Washington, a poky brown sweet gum seed, and a small rosette-shaped cone of deodar cedar.

*

The caw cawing begins even before my father’s tobacco-infused raspy kaaa kaaa kaaa slices through Delhi’s lacy blue skies. The birds wait, watching him place a ball of steaming hot white rice on top of the parapet wall and before he alights they swoop down: pecking, pulling, gobbling until the ball becomes air. We watch the crows from the shadows before fluttering to our spots at the table. In the northwest corner I call home, I become a flawed version of my father. When I remember, I quickly tear slices of bread and place them a few inches apart on the deck railing. Much caw cawing ensues; One arrives, then two. Sometimes one stacks the torn pieces on its beak and flies away to the dismay of my son, who fetches more bread for the birds waiting on the douglas fir branches. I don’t know if the birds followed me home or I followed them to theirs. For a moment the possessive pronouns dissolve into a puddle of awe.

*

Rituals are stories whispered through generations. What you hear, you pass forward, sometimes embellished. Somewhat like crows transmitting faces of whom to trust and whom to avoid to their progenies except with less known evolutionary benefits. Through my inherited stories of creatures, soft and wild, I find friends who share theirs. Our stories appear to have evolved from the same backbone. I relish our commonalities as if our ancestors had been neighbors when the Earth didn’t have walls or boundaries or words that slice open differences.

*

Researchers marvel at the intelligence and adaptability of crows but it’s their memory that baffles me. Not only do they recognize friends from foes, they impart this memory to their babies. I don’t know if the crows on the deck will remember my face but I know this: They are more than the collective noun of murder slapped on them, considering the boldness with which I have watched them chase away a bald eagle twice their size, an audacity of crows rings truer.

*

I think of words as rivers – always moving, sometimes changing course sometimes depositing unintended meaning, sometimes causing irreparable damage. When rivers change course as the Mississippi did more than 7000 years ago, forming much of the land that is south of Louisiana, scientists call it avulsion. When words change their meaning, sometimes drastically as in case of awful, which once meant full of awe, linguists refer to it as a semantic shift. Both rivers and words are known to disappear. Both leave scars. But there’s a difference – rivers only occasionally breach walls while words will not be contained. Banning books only increases interest in them as evidenced by Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. All we can do is let words be, let them erode, be eroded, until they are forgotten. If ever unearthed let them be reshaped by nature into something beautiful like pearls.

Author Vimla Sriram is a Seattle-based writer, shaped by Delhi. This means banyans and parrots will try to sneak into her essays even if, especially if, she tries to steer clear of them. She loves the Pacific Northwest for its gigantic Douglas Firs, leaning Madronas, and oat lattes. Her writing appears or is forthcoming in 100 Word Story, Wanderlust, Stonecrop Journal, Little Patuxent Review, River Teeth Journal, The Cincinnati Review and Panorama, the journal of travel, place, and nature.

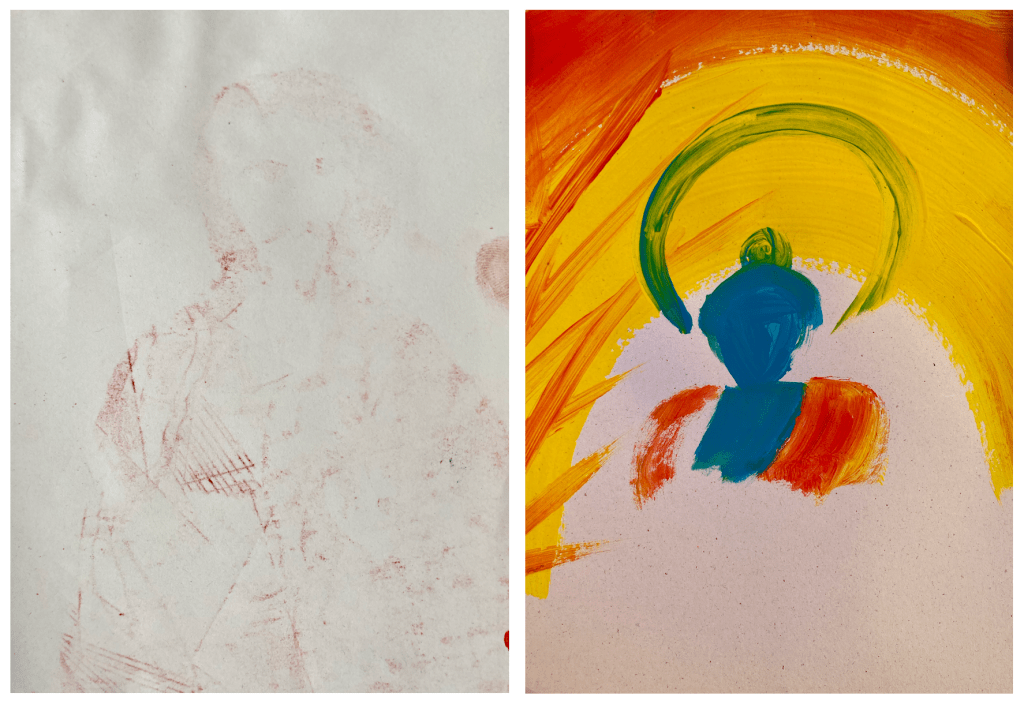

Artist Rowan Kilduff has had pictures appear on nanaoglobal.com; rewilding.org, ecozon@ España, and zestletteraturasostenibile.com, & poems and interviews in Rewilding Earth, Wingspan (Raptor Research Foundation US), Shufpoetry, The Irish Poetry Reading Archive, UCD, Camas Montana. His book, Wind to Space, will be out in 2024 from New Jersey publisher Read Furiously, and he has a book called Fire songs, sky songs, mountain songs (2022) with a foreword by Jack Loeffler (Headed into the wind). His work can be found on Flickr.com.